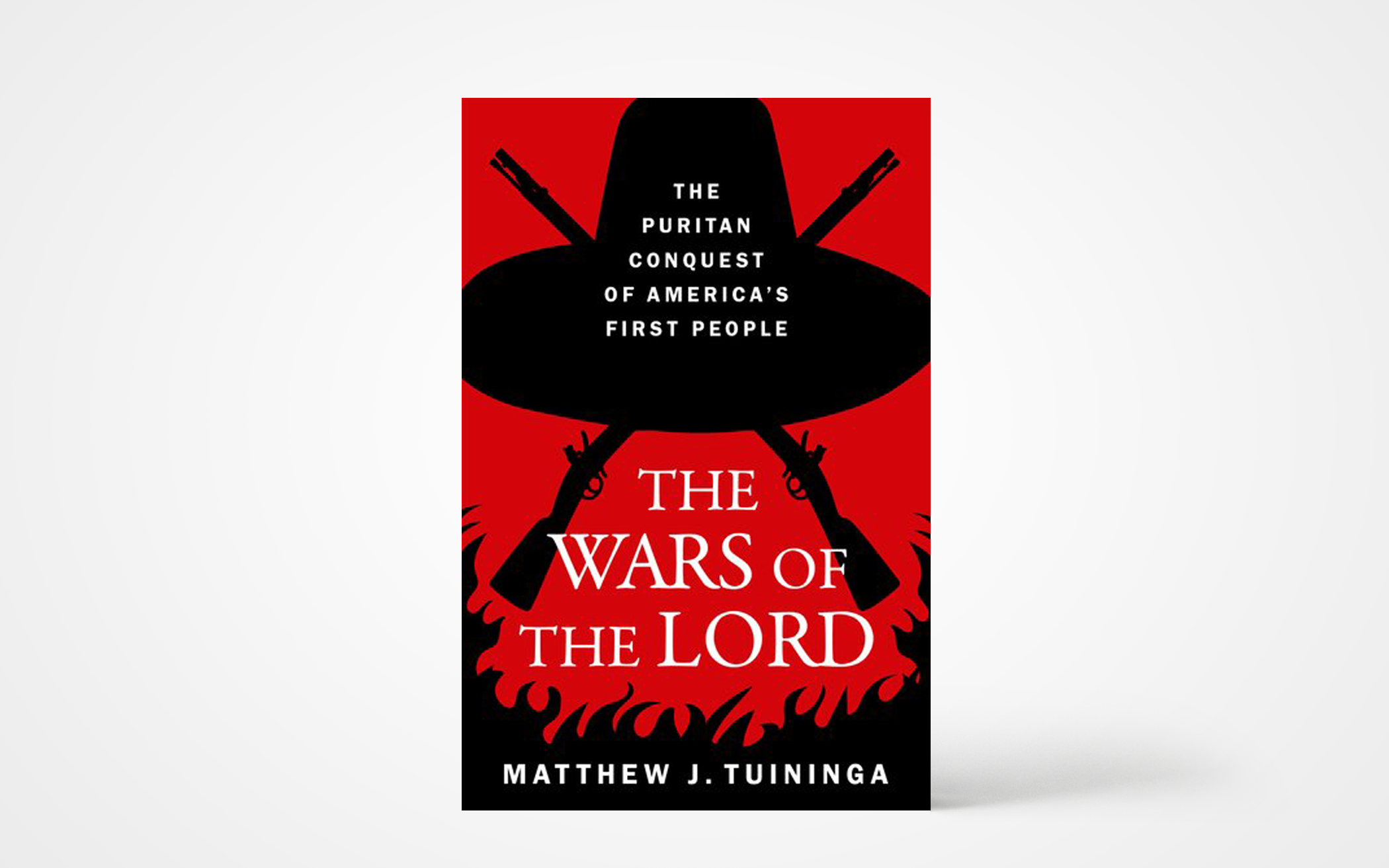

History is a complicated mess of noble intentions and selfish ambition. In The Wars of the Lord, Calvin Seminary professor Matthew Tuininga outlines what happened between 1620 and 1676 when the Puritans settled in New England and interacted with the various Native American peoples there. The book is a vast historical landscape of people and events where noble intentions of following the Bible mix with terrible flaws, giving catastrophic results.

Tuininga cleverly focuses on the facts with minimal commentary. Special attention is given to the perspectives of those who lived this history, effectively putting readers on the scene and helping those in the 21st century understand the pressures of 17th-century life. Their motivations are comprehensible even when despicable.

The little commentary Tuininga gives is in the introduction. The Puritans “believed that bringing Christ’s kingdom to the Natives would liberate them from darkness.” They believed they were in a fight against the devil to advance God’s kingdom through evangelism but also through English culture. What was envisioned to be spiritual and benevolent became “virtually genocidal.”

The goals of reaching Native Americans for Christ were muddied by the pervasive belief that the Puritans embodied the kingdom of God. Even their laws and government were shaped by the teachings of Scripture. Their ambition to follow Scripture in every facet of life meant the Puritans were Israel recast, tasked with conquering Native Americans for Christ. They regularly referred to themselves as “Israel” and Native Americans as “Canaanite.” Whether spiritual or military, these were the Lord’s wars. This is the primary theme of the book. The Puritan version of Christianity was “used to guide, interpret, and defend everything they did.”

The volume of research required to give a survey of this history was enormous. Each paragraph has a no-nonsense focus on what transpired, packed with the thoughts of the people involved and how events turned out. The reading is thick with details condensed from what could have easily been a multiple-volume anthology. The number of names and locations mentioned is overwhelming. Readers will do well to keep a finger between the pages at the beginning with maps and a list of key persons. Yet the writing is accessible. (Tuininga read the book to his children to ensure a wide audience.) While the content comes fast, Tuininga avoids the academic jargon for conversational prose.

The book is divided into three sections. The first section is on the Puritans arriving in New England and settling. Second is the missionary efforts by the Puritans to the Native Americans. The final section covers the all-out war between the English and Native Americans. Known as “King Philip’s War,” the fighting lasted just over a year but was per capita one of the bloodiest wars in American history.

More disturbing than the violence itself is the Puritans’ religious justification for their actions. In 1637, English militia massacred nearly all the Pequots at Mystic, including women and children. Afterward, one of the military captains raised the question, “Should not Christians have more mercy and compassion?” He then answered, “Sometimes the scripture declareth women and children must perish with their parents. … We had sufficient light from the word of God for our proceedings.” Another commander quoted Psalm 118 to describe the massacre: “It was the Lord’s doings, and it is marvelous in our eyes!” Such uses of Scripture haunt the mind long after setting the book down.

Since the author plainly reports on the history, protagonists and antagonists are elusive. Just as sin has universally infected the human race, ugliness is not limited to one group or another. There is plenty of villainy to go around. Killing women, children, and the aged was standard practice for everyone. (The Geneva Convention was still two centuries in the future.) The English were conquering colonizers, but warfare and bloodshed existed before their arrival. The English newcomers were an opportunity for one Native American nation to settle scores with another. Brutality was universal, but the Puritans had the added shroud of conducting their brutality in the name of Christ.

The most Christ-like heroes of this story are the “praying Indians” who persevered with the Christian faith despite all the racist persecution of the English. While the Puritans had the truth of the gospel, they could not overcome the dividing wall of hostility that Christ abolished. When warfare raised the anxious temperature, Puritans increasingly saw all Native Americans—believers and unbelievers, friendly and hostile—as treacherous and untrustworthy. Yet even the prejudiced Puritans could not help but be impressed by how “Christianly” the Native Americans were, “encouraging and exhorting one another with prayers and tears” while their parents in the faith relocated them to a barren island.

Upon closing the covers of this book, it is difficult not to conclude that all people are sinners in need of God’s grace. Even people as intentionally and purposefully biblical as the Puritans can still be products of their age, blind to their sins and tragically flawed.

The Wars of the Lord is essential reading not only for fans of American history but students of Christian history. Atrocities have been committed in the name of Christ not only long ago during the Crusades, or by Catholics during the Spanish Inquisition. Believers of the Reformed tradition have committed atrocities in the not-so-distant past in the name of Christ. Such a grave scriptural miscalculation challenges the believing reader to reflect on what ways we are blind products of our own time. (Oxford University Press)