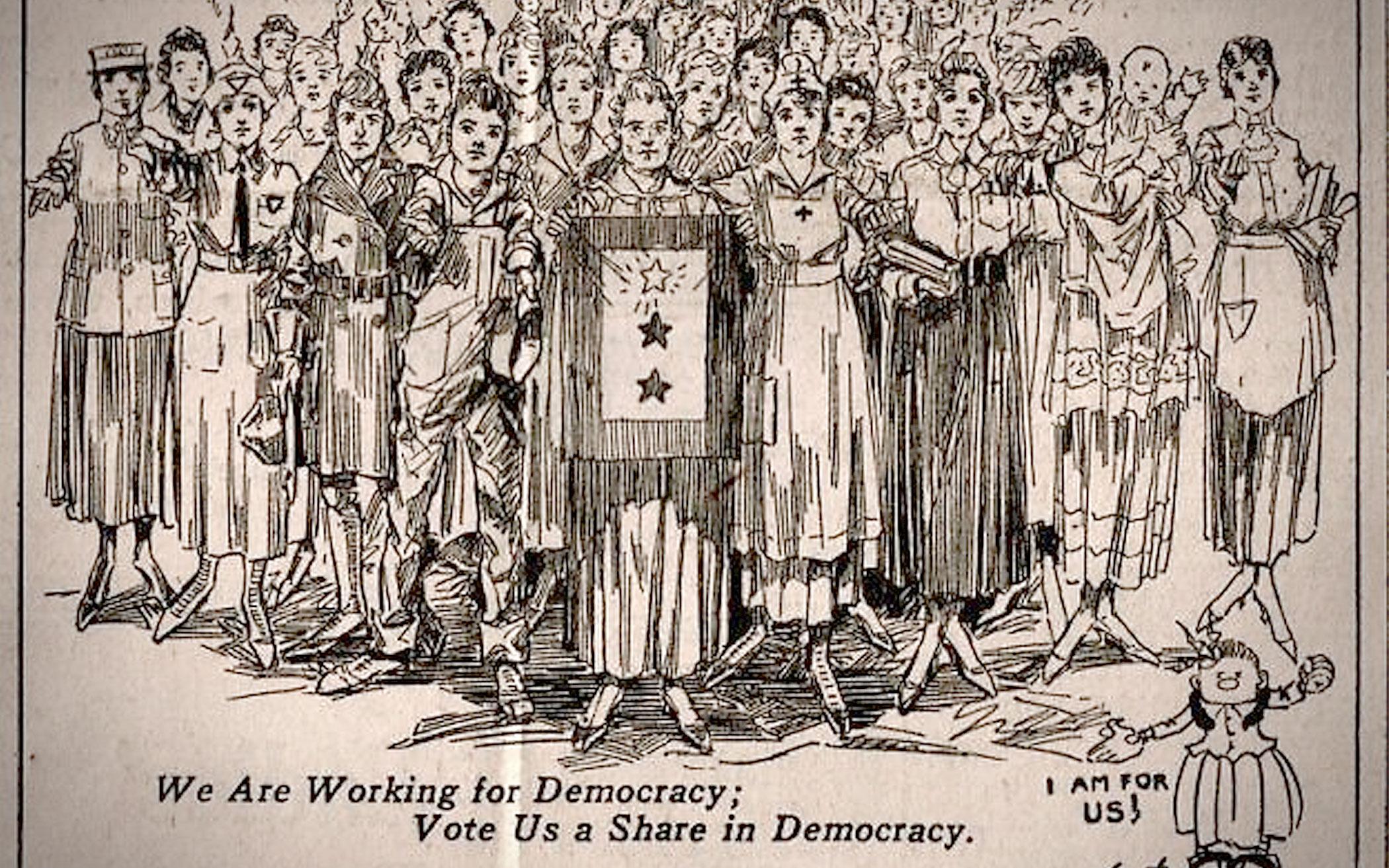

American women won the right to vote in 1920 with the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. Women were winning the right to vote in Canada at roughly the same time. For many suffragists, their Christian faith had led to participation in missions and reform movements such as prohibition and the abolition of slavery—and from there to seeking their right to vote. Their victory completed decades of activism, but suffrage also was just the beginning of an ongoing revolution for freedom and equality for women.

This ongoing revolution included the church. Should women have the right to vote in their churches? The suffrage question for the church was a consequence not only of political change, but of the Protestant Reformation of the 1500s and evangelical revivals in the 1700s and 1800s.

A majority in the Christian Reformed Church opposed women’s suffrage. In 1912 and 1913 in The Banner, for example, Jacob Vanden Bosch maintained that women’s suffrage would upend traditions in society, politics, and the church. The Bible taught that society consisted of families, not individuals. Votes by men represented not just the men themselves (as individuals), but also the women and children in their families.

Some Christian Reformed leaders promoted women’s suffrage, however. Rev. Johannes Groen, for example, argued that the “subordinate position of women” was not rooted in “creation” but was “a result of sin” and the “curse” on “mankind.” Men and women had different roles, he allowed, but women had a right “to assist in regulating” the things that affected their sphere. Without the vote they were reduced to “playthings.”

Groen’s was a minority view in the CRC in the 1910s. Some of his critics claimed that the matter was “confessional.” If so, then supporters of suffrage were transgressing Reformed teaching. They might be sanctioned, lose their ordination, and even be excluded from the church.

In 1916, the CRC synod decided that “women’s voting right is a purely political matter” and did not belong “on the terrain of the church.” CRC folk could actively support or oppose women’s suffrage.

In The Banner in August 1920, Reverend E.J. Tanis commented on the 19th Amendment. He expected CRC women to use their new rights. Nothing in Scripture clearly condemned “woman suffrage,” he observed. And it was “the consistent, natural, and logical development of the American system of suffrage,” in which “the individual citizen, and not the family,” was “the unit in the state.”

Suffrage in the Church

CRC magazines occasionally discussed the impact of women’s suffrage in the decades that followed. Women had avidly taken to voting and some had held public office, The Federation Messenger noted in 1930. Their presence had not purified American politics, however, as some suffrage advocates had hoped. Women too were sinners, after all, like men.

In September 1950 in The Banner, Henry Schultze connected women’s suffrage to social changes: women seeking roles beyond homemaking; married couples “needing” both spouses to work to pay for nice suburban homes; divorce becoming more common; and wives claiming authority equal to their husbands. Historians describe these trends—women seeking the same freedoms as men—as the “democratization” of the family. The price was too high, Schultze feared. Reformed Christians should continue “to fight the gods of selfishness and materialism.”

The ideals and habits associated with suffrage also began to reshape churches. Did men in church life represent their wives and children? Or should women and men represent themselves and have equal suffrage in the church? Articles in The Banner and other Christian Reformed magazines discussed these questions regularly beginning in the 1930s.

In 1934, for example, Henry J. Kuiper answered a question about widows being allowed to vote at congregational meetings. Voting was not mere consultation with consistories governing. It was part of church governance. Inviting women to vote would amount to “an announcement of their right to hold office as well as the men,” Kuiper argued, and contrary to Scripture.

The question did not go away, however. Women asked for the right to vote in some congregations. Some congregations supported it; others, concerned about uniformity in the church, wanted Synod to decide. Still others opposed it.

The CRC was not alone in addressing these issues. They were common among churches in North America and in Western Europe. The CRC continued to look to the Netherlands and to the Reformed Ecumenical Synod to assess trends and for biblical insights.

A synodical study in the early 1950s concluded that “it would be unwise” to “make a pronouncement” on the question as there was not “sufficient clarity” among the churches. It also noted that the RES supported women voting at congregational meetings. Women shared with men the “office of believer.” Their voting was “fitting and proper.” Local customs should be considered. Articles in The Banner and other CRC magazines commented on the issue regularly in the 1950s.

In 1955, Synod again appointed a committee to study women voting in congregational meetings. In 1957, aware that there was no consensus in the CRC, it approved a local option. Women “may participate” with the same rules that governed the participation of men, it decided. However, “the question as to whether or when” women would be “invited” to partake was left “to the judgement of each consistory.”

Requests by women to partake more fully in the life of the church along with support from classes and congregations lay behind Synod’s decision. Biblical declarations of equality of women and men as believers before God made it difficult for synod to come to simply deny women’s suffrage. Texts that seemingly forbade authority by women over men and ordained different roles for them in church and society weighed heavily too. Already in the 1950s, however, the question was whether limitations on women’s roles were social prejudices or God-ordained. The decision in 1957 was equivocal, but it marked a sea change.

Making Room for Women

George Stob, for example, had been wary of women’s suffrage in the church in 1952. But in 1957, he argued that the church should not “keep Christian women from the councils of the church” or “circumscribe their activities.” It should instead “use their talents and abilities to fullest advantage.” The New Testament, he said, called the church to sweep away forms of backwardness and make room for women in the “household” of the church.

The local-option compromise of 1957 meant that the issue continued to come up on occasion. In 1985, The Banner published a story about a woman from Indiana who had protested to her classis the exclusion of women from voting in her congregation.

By the 1970s, the question increasingly was about women holding the church offices of deacon, elder, or minister. In the 1980s and ’90s, the CRC similarly would take a local approach to women holding church offices, allowing classes leeway about implementing women’s ordination.

From the Inside Out

The way I’ve written this sketch of women’s suffrage suggests that the equality revolution infiltrated churches from the outside. But that’s only part of the story. The opposite is true too. The Reformation itself set off an unintended revolution that undermined traditional authorities and spurred the individualism of modern life that critics of women’s suffrage like Schultze lamented.

Martin Luther’s stance before German political and religious authorities in 1521 is illustrative. “Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason,” he declared. “I cannot and will not recant anything since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. May God help me.”

What was the authority that Luther appealed to here? Was it Scripture? “Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures.” Or was it his individual conscience? “Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures.” Was it effectively both?

Luther himself rejected applying “Christian freedom” and individual conscience to society and politics, but other Reformers make such connections. Whatever Reformers like Luther and Calvin intended, these ideas encouraged both religious, social, and political revolutions in the long run.

Could any man be denied the right—indeed, the obligation—of conscience in matters of religion, society, and politics? This was a revolutionary question. Could any woman be denied? This was the natural next question and even more revolutionary.

Evangelical revivals in the 1700s and 1800s inspired individualism in society and democracy in politics, continuing what the Reformation had started. Women sometimes led them. At the same time, the ideals and habits of capitalism and democracy accented individualism in Christianity. “Jesus is my personal savior” is both a Christian confession and a modern declaration.

Protestant Christians have been wrestling since Luther and Calvin’s time with tensions between individual freedom and conscience on one hand and community and confessional traditions on the other. Traditions that emphasize covenanted community, such as the CRC, also are shaped by appeals to individual conscience and histories of church splits. Calvinists who confess a theology of election nonetheless require a personal profession of faith for full membership. Parents’ choice to baptize their children is not enough. At some point, women and men alike must decide for themselves what to confess and whether to join a church. And they can always choose otherwise.

From a long point of view, then, women’s suffrage in the CRC in the 1950s was a product of the Reformation and democratic revolutions. Both have shaped the modern experience of individual choice and the tensions that result in trying to reconcile freedom and conscience with community and claims to authority.

About the Author

Will Katerberg is a professor of history and curator of Heritage Hall at Calvin University in Grand Rapids, Mich. He is a member of Church of the Servant CRC in Grand Rapids.