If one spends 23 years living and working with Navajo people in western New Mexico, as I did, one will come across stories that need to be told. A cross-cultural setting highlights the uncommon—even remarkable—events of people and places that those of us reared in the prevailing culture find it difficult to apprehend. Such is the story of Julia Jumbo from Toadlena, N.M.

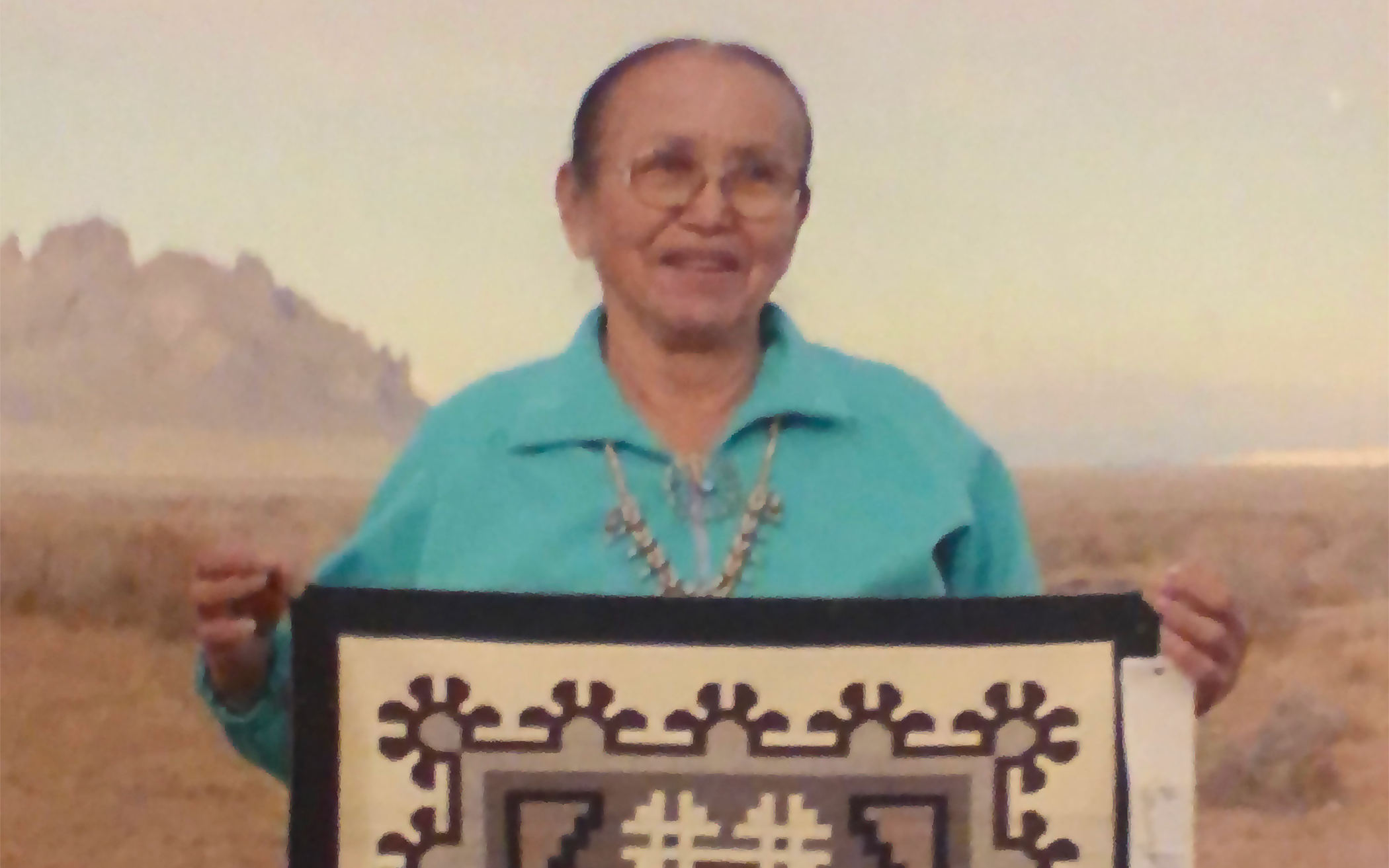

Julia Jumbo was a weaver—indeed, a master weaver. Her weavings are not merely Navajo rugs, as beautiful as they are; rather, they are spectacular tapestries—works of art worthy of awe and wonder. The tightness of the weave (120 threads per inch) and the precise symmetry enabled Jumbo to often place highly in art shows, and she earned the Southwest Association for Indian Art’s Lifetime Achievement Award. She is simply the finest of the master weavers.

Jumbo was born in 1928 “in the bush,” meaning she was born as her mother was herding sheep—not all that unusual on the reservation. Jumbo’s mother died when she was 7, and she was thereafter raised by her grandparents. She openly acknowledged that she had a difficult childhood, was “treated mean,” and “denied school and made to work.”

Of further note, Jumbo was Christian Reformed and attended the Toadlena mission church established in 1910. Her pastor was Rev. Jacob Kobes, who with his wife, Trina, served the Toadlena community for 37 years. Jumbo lived four miles from the church. Until she finally got a pickup truck in 1965, she most often walked to church on the rutty roads. Otherwise she depended on horses and wagon or on Rev. Kobes coming with his truck.

How is it that one raised in these circumstances rises to such artistic distinction?

At age 9 or 10, Jumbo made herself a smallish loom and taught herself how to weave. She took her first rug to the trading post, and, not knowing how much to ask, accepted a bag of candy as payment. Such was the inauspicious start of the CRC’s greatest master weaver.

Jumbo’s aunt was a notable weaver who became someone to imitate. In particular, Jumbo picked up her aunt’s idea of surrounding her weaving with rosettes. Jumbo and her daughter Serena were and are the only weavers to perfect and carry that pattern forward. It became a trademark. By the time Jumbo was in her early 30s, she had entered a prizewinning rug at the Gallup Indian Ceremonial.

Serena described to me her mother’s work and habits as such: “They are all tapestries. I remember all the rugs she’s woven. She always had wool in her hands, spinning and carding the wool and sitting on the floor, busy weaving.” She remembered when a fire at their home destroyed two tapestries ready for competition at the renowned Santa Fe Indian Market.

Jumbo also experienced much deeper pain when she lost two sons in a car crash in 1971. The girls remember the deep grief of their mother surrounding the accident. The oldest son, a Vietnam veteran, used alcohol to address his post-traumatic stress. Serena said Jumbo cried so much “her eyes were swollen shut,” and she was disappointed that more church members did not come by to share in her grief. These days Serena makes it her ministry to visit the families dealing with sorrow, Bible in hand.

One cannot help but wonder how these tragedies, along with Jumbo’s difficult childhood, affected her spiritual life. Jumbo died in 2007, but her three surviving children have shared some of their memories with me.

Navajo families in the 20th century were often disrupted by poverty, transportation difficulties, language challenges, boarding schools, and the cultural persistence of traditional religion. Yet Jumbo’s children Kee, Serena, and Julie Marie all are faithful believers thanks to seeds planted in their lives by their Christian mother, earnest missionaries, and religious instruction at school.

Jumbo’s husband was not a Christian, nor did the family participate in traditional Navajo religion. Yet, Kee remembers his father often saying “God never dies.” He seemed not to be opposed to the family’s Christian instincts, Julie remembers, and even was the one who took the lead in enrolling her and a brother in the CRC-sponsored Rehoboth Mission School.

Through it all, Jumbo kept on weaving. Historian Mark Winter wrot[1] [2] e, “Julia Jumbo said the hardships of her youth made her ‘try harder.’” Her work was typical of weavings from the Two Grey Hills region—that is, it featured shades of black, white, gray, and brown. But because Jumbo had to sell her work to survive, her children possess none of her tapestries.

Is it fair for the CRC to claim this renowned artist as one of its own?

In those early decades of the CRC mission effort in the American Southwest, there was all too great a gulf between the culture of the white missionaries and the Indigenous cultures they came to serve. The white folks were dominant, and Native people, at least early on, were generally compliant. Worse, there was too often a lack of respect for the Navajo language and culture and for Native leadership.

Given their geographic and cultural distance from denominational leadership, the Navajo CRC people and congregations were easily overlooked and marginalized. In that context, in the obscurity of Toadlena, N.M., lived one of the finest Navajo artists—one affiliated with a Christian Reformed church. It is altogether fitting that at long last Julia Jumbo is recognized and honored by her church for the God-given, Spirit-led creativity and discipline reflected in her impressive body of work. Could it even be that Julia Jumbo’s artistry is unsurpassed within our CRC tradition? Visitors to the art gallery at Calvin University in Michigan or Rehoboth Christian School in New Mexico will surely see the quality of her work, celebrate its beauty, and wonder how it was essentially out of sight for several decades.

But now it is being noticed, and in it we shall see the Light that flowed from the hands of Julia Jumbo.

About the Author

Ron Polinder is a retired school administrator of Rehoboth (N.M.) Christian School and Lynden (Wash.) Christian School. He is an elder at Sonlight Christian Reformed Church in Lynden.