My friend Michael Elliot has been in prison for 27 years. He tells me that prisoners suffering from mental illness sometimes cause life to be difficult for their fellow prisoners. For example, whenever a mentally ill prisoner “bugs out” or exhibits behavior triggered by the illness, especially through physical violence, it becomes more and more a part of everyone’s reality who shared in the experience.

“Recently a prisoner sitting next to me in the prison law library quietly stood up, raised his metal chair over his head, walked across the room, and hit another prisoner with it,” he said. The victim of the chair strike was facing the opposite direction and did not see the attack coming. Afterwards, the injured individual told Michael that he did not know or speak to the aggressor.

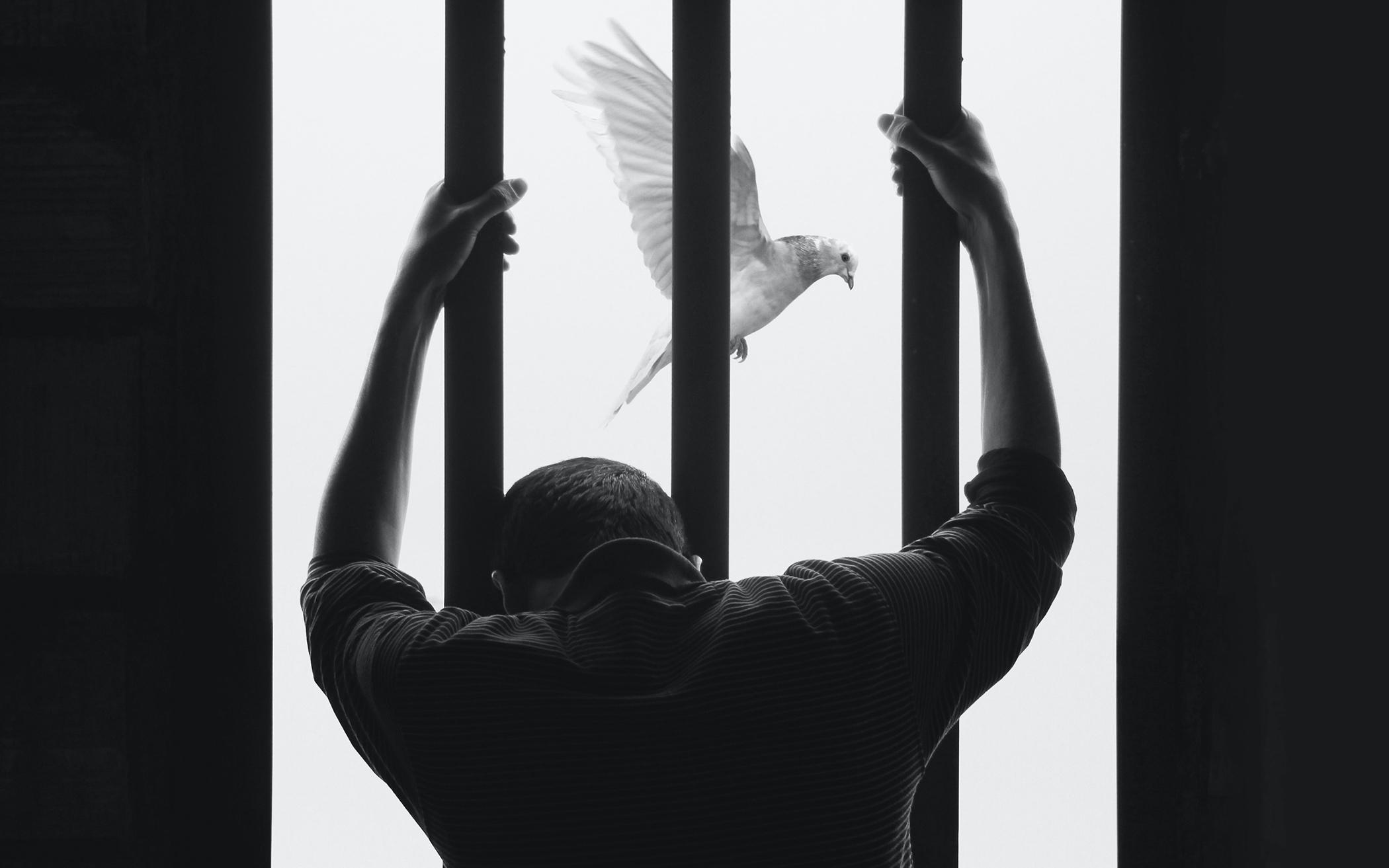

On another occasion, as Michael was on his way back from the yard to his cell, he noticed another prisoner who gave him a strange look and then walked over and said, “I know you want to kill me!” My friend did not know the other prisoner, but afterward felt the need to keep an eye on him and on everyone he did not know. Being locked up away from family and friends, unable to pursue a career or live a “normal” life was hard enough, he explained. He was not prepared to live among criminals who were mentally unstable.

“Living in close quarters with mentally ill individuals doesn’t allow one to adjust, much less learn to adapt to a normal social environment,” he said. Sometimes, he added, people with mental illness scream throughout the night, making it difficult for everyone to sleep. Clearly the prison experience is far worse for people who do not suffer from mental illness when they are housed with mentally ill people.

With the advent of the war on drugs, the U.S. prison population has risen to 2.3 million, or 698 per 100,000, more than all other countries put together. (In Canada the number is 139 per 100,000.) A substantial proportion of these inmates are mentally ill and are held with little to no access to treatment. In recent years, prisons have added some clinical staff to provide treatment, but caseloads are high and clinicians are not available in all prisons. Housing prisoners who do not suffer from mental illness with those who do was a decision made by high-level administrators and politicians who failed to study the consequences. This situation has now been going on for over four decades.

Most reports that I have read indicate that 30 to 40 percent of the people in prison are mentally ill. My friend Michael estimates that the number is at least 80 percent.

Is there a solution to this brutal situation? None of the following ideas will solve all the problems by itself. But cumulatively they can eliminate most of the problems.

- Develop mental health services in communities, inpatient, and outpatient programs. These programs would cost less than the approximately $36,000 a year per person cost of incarceration in prison. Jail costs are even more; and some local jails have the inhumane practice of charging room and board to the people they hold. These programs would have to be implemented by mental health agencies using both state or provincial and federal funds. Churches could develop programs to help former prisoners adjust to society while being exposed to Christian values.

- Increase in-service training for prison staff to deal more effectively with specific needs of incarcerated people who are mentally ill.

- Reduce the number of people sent to prison. Increase restorative justice programs and increase the age at which young people are considered adults. Examine the sentencing pattern in each county, as there are some extremely long sentences. In Sweden, the legal maximum is 20 years.

Reducing some sentences seems appropriate, but maybe not for pedophiles. Many believe that their tendencies are permanent. They need confinement or close supervision throughout their lives. - Increase the number of activities that reduce recidivism. For example, in Texas, introducing toastmaster clubs into prison reduced recidivism by 50 percent. Colleges teaching four-year courses reduced recidivism to 4 percent. Fifty years ago, Gerrit Hynes was the administrator of the Michigan Department of Corrections. He introduced prison industries that produced furniture for public agencies as well as enriching the prison atmosphere in other ways. During his tenure recidivism rates sharply decreased. There are also Christian programs in Michigan, for example, including at Hope College and Calvin University, that reduce recidivism.

These suggestions must be implemented by elected and appointed officials. But what about ordinary Christians? In Matthew 25:36, Jesus said, “I was a stranger … sick and in prison, and you visited me.” This may be the time that Canada and the United States are willing to try to address the needs of prisoners who are mentally ill and to avoid the dangers posed by lack of treatment to the whole prison population. As a result, they and all prisoners will be more inclined to feel as if they are part of the human race.

About the Author

Jake Terpstra is a retired social worker, former director of three child welfare agencies in Michigan and a child welfare specialist in the U.S. Children’s Bureau, from 1977 to 1997. Jake is the author of Because Kids Are Worth It. He lives in Grand Rapids, Michigan.