The Banner has a subscription to republish articles from Religion News Service. This story was first published on religionnews.com Sept. 9, 2021.

The melody that changed Keith Getty’s life was first scratched out on the back of an electric bill in a humble flat in Northern Ireland.

This isn’t great, he thought at the time.

But it was the best he could come up with. So he sent a recording of the melody on a CD to Stuart Townend, an English songwriter he’d met a few months earlier at a church conference, in hopes Townend might be able to turn the melody into a serviceable hymn.

Getty was right.

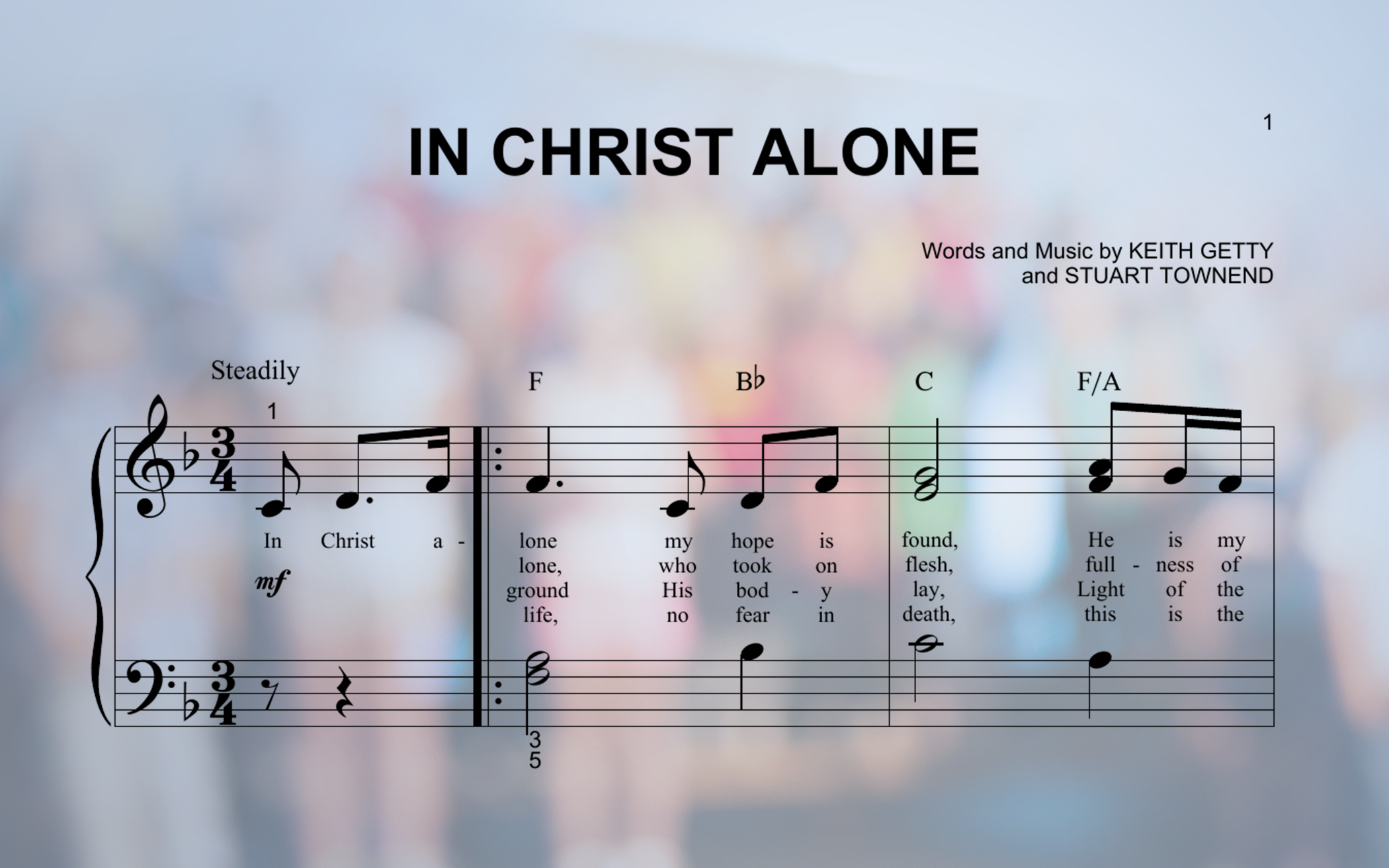

That melody became the basis for “In Christ Alone,” which was released in 2001 and has become one of the most popular songs in Protestant churches, according to Christian Copyright Licensing International, which tracks songs sung in churches. The song also launched a new era of modern hymn writing.

All of which came as a surprise to the tune’s authors.

In a 2016 interview recounting the origins of “In Christ Alone,” Townend said there was nothing memorable about his meeting with Getty.

“We got together, we had a coffee, nothing particularly eventful happened,” Townend recalled. “He said he’d send me a CD with some of his song ideas. … It arrived, and I wasn’t expecting anything.”

Then he popped in the CD and immediately changed his mind. He eventually called Getty and the two talked about writing a musical version of a church creed that would recount the story of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus.

Singable Melody, Theological Reflection

The song originally started with the line “My hope is found in Christ alone.” Getty suggested switching the verse around to start with “In Christ alone.” After some hesitation, Townend did so, and the song came to life. Getty has described Townend’s lyrics for the song as “absolutely brilliant,” capturing the story of Christian faith in a powerful and lovely way.

Getty has sometimes called “In Christ Alone” a “rebel song”—a kind of protest against the more contemporary worship songs that sound more like pop music than traditional hymns. It was the first of a series of modern hymns he’s helped write, combining singable melodies with theological reflection.

He believes they are the type of songs Christians need in a complicated and ever-changing world.

“If we’re going to build a generation of people who think deep thoughts about God, who have rich prayer lives, and who are the culture-makers of the next generation, we need to be teaching them songs with theological depth,” he said in a 2016 interview about his approach to hymn writing.

Getty and his wife, Kristyn, who perform together and tour with their four kids and an Irish-themed band, are back in Nashville, Tenn., after nine months on lockdown in Northern Island, where they have a home. Being back in Ireland was respite for the Gettys after a decade and a half of touring, recording and building a music publishing business. They spent much of the time walking on beaches, hanging with their kids and hosting weekly hymn sings on Facebook Live.

They returned to Nashville ahead of their annual Sing! conference, which is expected to draw about 6,500 people, with an additional 40,000 streaming online. The event, scheduled for Sept. 13-15, has drawn more than 16,000 people in person in the past.

Presbyterian minister Kevin Twit, founder of Indelible Grace, a Nashville music company that sets traditional hymns to new tunes, is a big fan of the Gettys. He sees “In Christ Alone” as a marriage between well-written and inspiring lyrics and a hymn tune that’s both compelling and flexible. The song works as well on a pipe organ with a choir as it does in a small church with a guitar and a handful of voices, he said.

“That’s hard to do,” he said.

Twit, who leads the Reformed University Fellowship at Belmont University in Nashville, said “In Christ Alone” appeared on the scene just as a number of younger evangelicals were looking for songs with more theological depth than the contemporary songs they had learned in church growing up. Getty, Twit said, understands the way songs people sing in churches shape both their theology and the way they live their lives.

“I think he really gets that worship is formative,” he said.

The Rev. Constance Cherry, professor emeritus of worship and pastoral ministry at Indiana Wesleyan University, believes “In Christ Alone” has succeeded by combining the traditional structure of a hymn with the kind of instrumentation used in more contemporary worship settings.

She said the structure of a hymn makes it easier for hymn writers like Getty and Townend to dig deep into a theological topic.

Cherry also appreciates that the Gettys are focused on creating hymns that make it easier for congregations to sing together. That’s a lost art, she said, in a time when many more contemporary worship songs are modeled after what is popular on the radio. While she appreciates contemporary praise songs, she said they are often focused more on the musicians than on the congregation.

“Every worship song in any worship service has one goal—and that is for the people to sing,” she said.

Brian Hehn, director of the Center for Congregational Song, the outreach arm of The Hymn Society in the United States and Canada, also points to the flexibility and beauty of the melody of “In Christ Alone” for the hymn’s enduring success. The melody falls in a comfortable range for most people and is simple and accessible while still intriguing to listen to. And it works for praise bands and choirs alike—a key to a successful congregational song, he said.

Townend’s lyrics, Hehn added, are beautifully crafted and full of nuance. They walk the worshipper through the life of Jesus, from the Incarnation—“Fullness of God in helpless babe,” as the hymn puts it—to the death of Jesus and then his resurrection. The song also connects God to the life of worshipers—“from life’s first cry to final breath.”

Because of that, the hymn works in a variety of settings, from a Christmas or Easter celebration to a regular Sunday service.

The song also contains surprising theological complexity, said Hehn. It’s perhaps best known for a line about the wrath of God being satisfied in the crucifixion, which reflects a theology known as penal substitutionary atonement that’s commonly accepted in evangelical churches. But that has led other churches to change the lyrics of the hymn—and caused the song to be dropped from a Presbyterian Church (USA) hymnal after a proposed lyric change was rejected.

But “In Christ Alone” also references the Christus Victor view of the atonement, which celebrates Jesus’ victory over the grave, and the ransom view of the atonement, which stresses that God purchased forgiveness of human sin from the devil with the sacrifice of Jesus.

“I find that wonderfully broad,” he said.

While congregational singing may be on decline in American churches, Hehn said it remains vital in many churches around the world. And there will always be a need for songs like “In Christ Alone.”

“No matter how you interpret the Bible, it is impossible to get around the fact that we’re supposed to sing together,” said Hehn.

© 2021 Religion News Service

About the Author

Religion News Service is an independent, nonprofit and award-winning source of global news on religion, spirituality, culture and ethics.