Holy Week invites us to dwell in between. From Palm Sunday to Easter, we move between our daily lives and the devotional immersions of the week, placing ourselves briefly into each scene of the Passion drama. All along, we remain aware of what’s next: the palm branches will lead to the upper room, then to the Good Friday tenebrae candles, then to the processionals of Easter Sunday. Even amid our devotional immersion, we know what’s coming.

Holy Saturday is the most in-between place of all because here the scriptural drama holds its breath. There is no scene in which to place ourselves, only silence. The disciples and the women “rested in obedience to the commandment,” says Luke (23:56), and that’s all we know. Jesus is in between too, between the burial and the rising, silent in the grave. Some recent theologians have wondered whether to imagine the second person of the Trinity, from Friday afternoon to Sunday morning, as dead, dead, dead.

How could one possibly ritualize this day, then? The church in its traditions has not directed us to imagine ourselves with the disciples on Holy Saturday, perhaps because one can only imagine them in a state of bewilderment and despair. They had experienced the horrific crucifixion of their Lord, and they could not begin to imagine what was coming next. Instead, the church has filled that silent place by inviting us to reflect on the harrowing of hell.

The notion that Jesus was busy on Holy Saturday goes back to ancient sources, some as early as the second century. True, getting to the harrowing of hell from the whisper-thin scriptural warrant requires some imaginative speculation. But Tertullian, Hippolytus, Ambrose, Chrysostom, and other early theologians took the idea seriously, and it was a standard topic of reflection in the European Middle Ages, including in Anglo-Saxon Britain, where the English term “harrowing” originated.

The word “harrow” is derived from Old English and has two related meanings dating back to at least A.D. 1000. One comes from farming. To harrow is to break up clods of dirt in preparation for planting. One might plow to turn over the soil, but to really churn it up, you need to drag a harrow over it. Modern farm harrows are vicious-looking contraptions that churn soil with toothed, spiral blades. Violence is inherent to the other meaning, too: to plunder, rob, or spoil. To harrow is to tear a place to pieces, to really wreck it up.

So the harrowing of hell gives us an energetic, even threatening Jesus who does not rest in the tomb but steps down from the cross and strides right on to the next task, this one requiring some real farmhand muscle. This is the same Jesus we saw combating the Pharisees with deft scriptural maneuvers, the Jesus who tore up the temple in a righteous rage. Descending into hell, this Jesus is ready to wreck the place up.

One can see why this idea has appealed to the devout over the centuries. For the more literal-minded, it explains where Jesus’ spirit was while his body lay in the tomb—helpful to preserve the idea that God cannot die in any sense we understand. It also explains how Old Testament saints can be saved into blessedness—they waited in Sheol until Jesus rescued them. For the more literary-minded, Jesus’ descent into hell corresponds to the epic archetype of the hero, who must at some point descend into the underworld.

In that greatest underworld epic of all, Dante’s “Inferno,” the shade of Virgil describes the harrowing of hell from the point of view of a condemned soul. He explains to our pilgrim protagonist that when he (Virgil) first arrived in Limbo, it wasn’t long before a Great Lord (Italian: possente, mighty one) came crashing down there and carried off the shades of Old Testament heroes. Virgil, however, along with his compatriots among the noble pagans, is stuck in Limbo forever, where, he says, “we have no hope and yet we live in longing.”

You would think the Reformers would appreciate a Jesus so industrious he doesn’t even rest on the Sabbath after his crucifixion, but Calvinists have tended to tone down the harrowing and focus on Jesus’ suffering on our behalf. Thus the Heidelberg Catechism glosses—explains and annotates—the “he descended to hell” clause in the Apostle’s Creed as a way of describing the utter desolation of Jesus on the cross, thus assuring us that Jesus can redeem us from our own places of “deepest dread and temptation.”

Perhaps Calvin and his followers were worried about how the harrowing of hell might make Jesus out to be some warrior-style conqueror, and there are good reasons for caution there. But I have learned to consider seriously the psychological and spiritual wisdom of the ancient church, especially when that wisdom persists in the devotion of Roman Catholic and Orthodox Christians today.

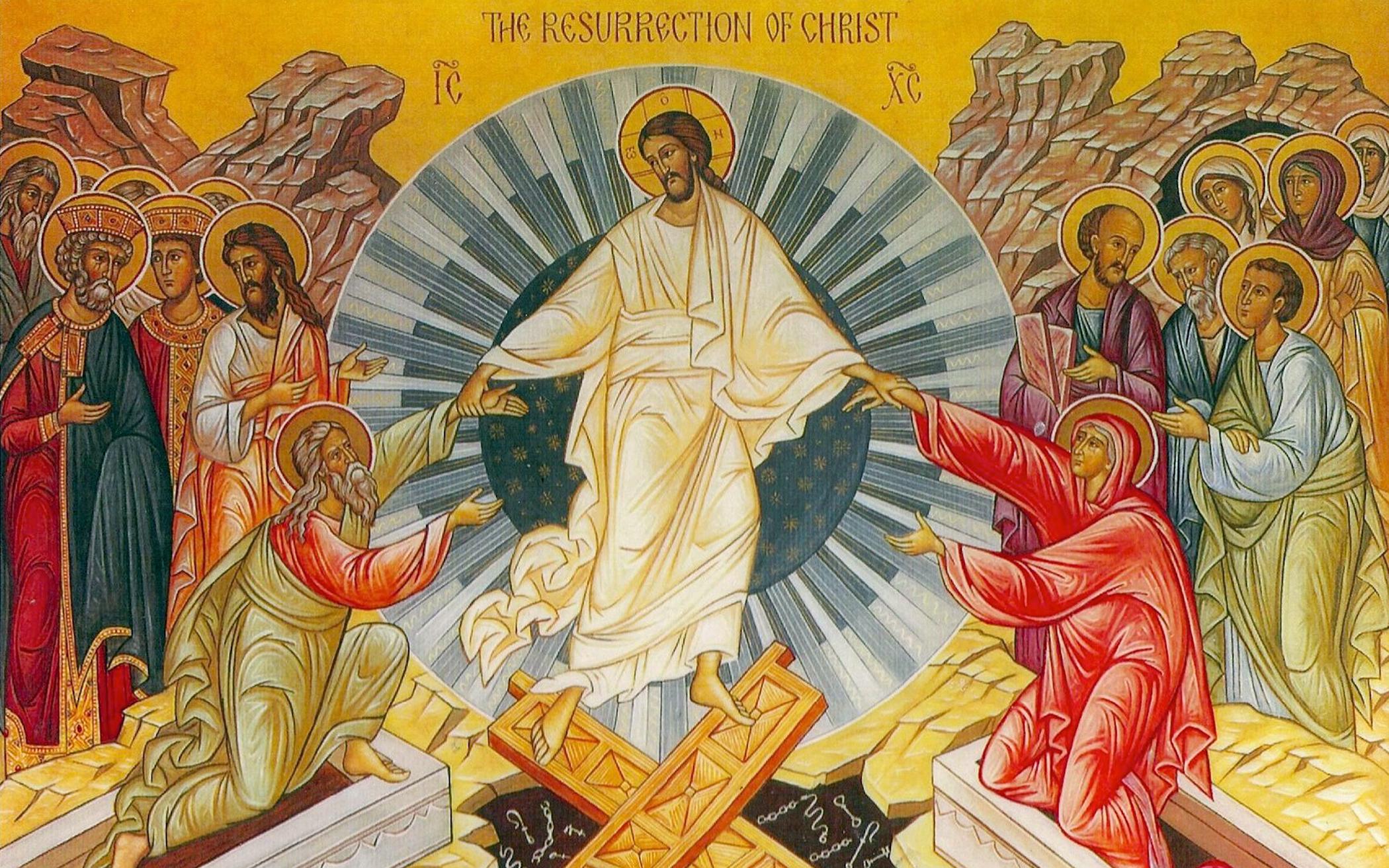

Why has this Holy Saturday doctrine persisted? I think because we need it. However poetic and allegorical you want to make Jesus’ Saturday adventures, we need to know the theological truth beneath: Jesus conquers death and hell. We need to see Jesus as Orthodox icons depict him: standing there astride the abyss, dragging Adam and Eve up by the wrists, “radiant, in spotless white, standing straight, but leaning back against the weight of lifting them,” as poet Scott Cairns writes. We need to see him defying hell as it exhales a last filthy breath.

We need this because here we are, in between. In between suffering and redemption, pain and hope. I doubt the disciples had much hope on that first Holy Saturday. Unlike them, we know what’s supposed to happen on Easter Sunday. We, at least, have a wobbly hope. But is it real? Are we fools? In this Limbo, are we doomed to have no real hope, only to live in longing?

Isn’t what we fear most that God is silent, doing nothing? We fear, in our Saturday moments, that God is too weak to act on our behalf or is indifferent to our pain. That we are completely and utterly on our own. That no one cares and our suffering is meaningless and inescapable. That our Easter hope is ridiculous. That God is dead, dead, dead.

I think of those who, even after Easter Sunday, will still be in this in-between, Saturday place: friends whose bodies have been harrowed by cancer. Elderly folk in the nursing home, some of them every day sliding deeper into a living oblivion. And all of us, whose troubles and sorrows will not suddenly disappear because the liturgical calendar turns and the lilies appear on the chancel.

It’s a great mystery, the reality of the Trinity during the time between “It is finished” and the risen Christ’s appearance in the garden. I choose to meditate this Holy Saturday on the busy Jesus, who crashes into hell and tears the place up, dragging the saints out by the wrist. I’m going to believe that when Jesus takes a harrow to our hearts and our teeth jitter and we feel churned up, the end result is that things will grow better there, and the seed that falls to the ground will rise up, imperishable.

Editor’s Note: A version of this article was previously published on the author’s blog at debrarienstra.com.

About the Author

Debra Rienstra is a professor of English at Calvin University, Grand Rapids, Mich.