When you are at a concert, do you ever close your eyes? Sometimes, you want to let the music sink in. But with some concerts, it’s impossible to seize the full emotion of a singer unless your eyes are wide open.

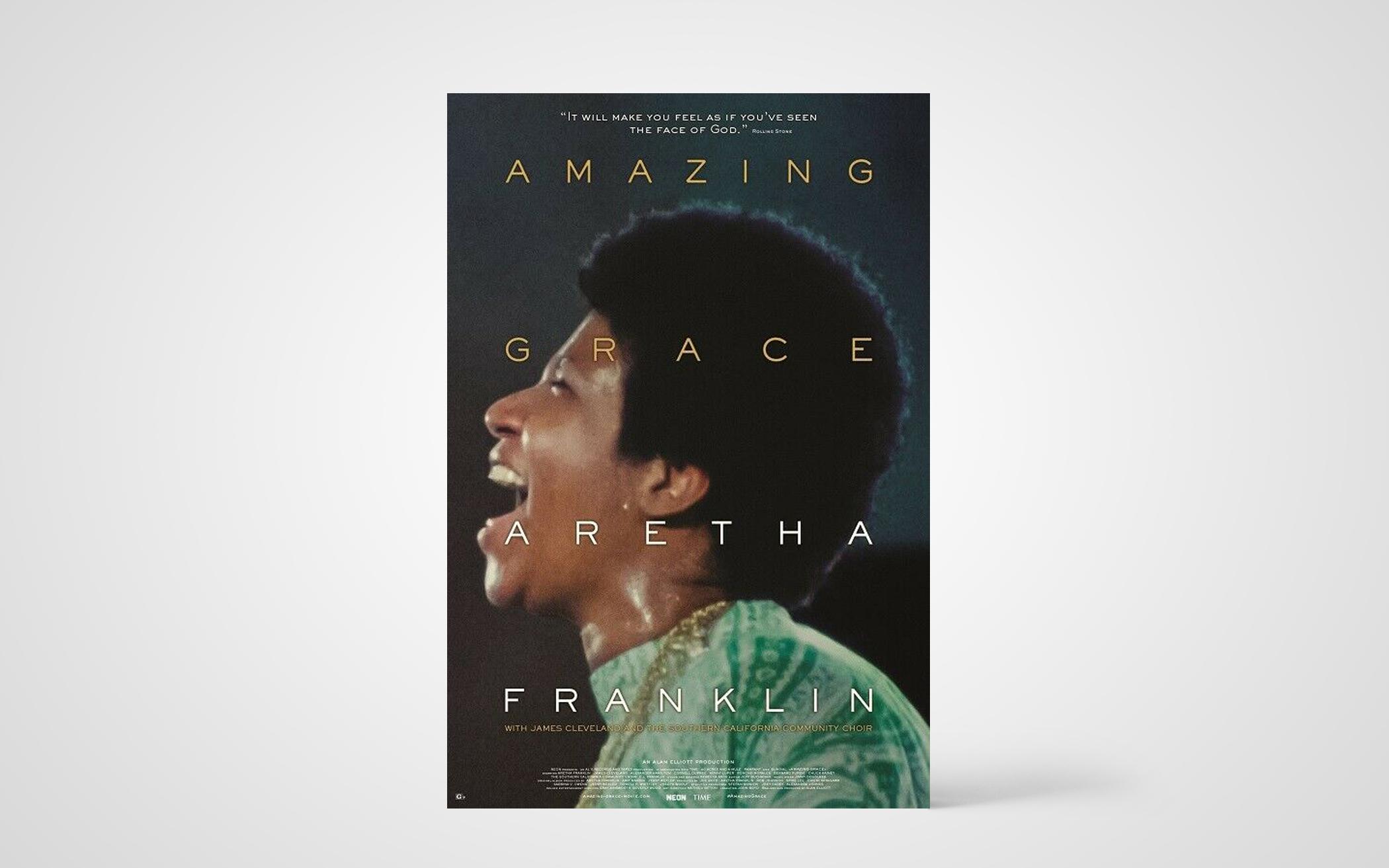

Such is the case with Aretha Franklin’s chart-topping album “Amazing Grace.” Recorded in 1972 at the New Temple Baptist Church in Los Angeles, the album is a testimony to Franklin’s incredible artistry.

But for almost fifty years, we have had only half the picture.

In 1972, then-up-and-coming director Sydney Pollock filmed the live concert, but the project languished in the Warner Bros. vaults for decades. The reason? Technical difficulties. Pollock and his crew forgot to use a clapper, the type of board that an assistant holds open to say “scene 1, take 2,” and then claps shut. As a result, it was impossible to know how to sync the sound recording to the concert footage.

Thanks to technological advances, producer Alan Elliott was able to have the music sync to the images. Franklin, however, objected to the film’s release for reasons that remain unclear. After her death last year, her family agreed to have the film released.

“Amazing Grace” begins by fully setting the stage. We see the traffic of 1970s Los Angeles, audience members entering the church, and the silver-vested members of the Southern Californian Community Choir and director Alexander Hamilton prepping themselves in the wings. The Rev. James Cleveland, a gospel star in his own right, introduces Franklin, who enters regally from the back of the church.

And when Aretha Franklin sings, it’s glorious to see her mix of calm control and full-hearted feeling, especially with the title song “Amazing Grace.” For 10 minutes, she teases out the meaning of every line in the hymn. The choir sits down to listen. James Cleveland asks the choir director to take over at the piano so he can gather his tears. As Franklin’s voice rises and the sweat pours from her face, members of the choir stand up and shout in praise and encouragement.

The mostly African-American audience appears self-conscious when faced by Pollack’s lumbering cameramen. When the first-rate band picks up the pace, inhibition disappears and there is dancing in the aisles. And at the back, Mick Jagger and Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones also move with the music. They obviously understood something historic was happening.

At one point, James Cleveland invites the Rev. C.L. Franklin, Aretha’s father, to speak. As you can hear on the concert album, he proudly declares that, despite all of his daughter’s popular success, “she has never left the church.” In the film, we also see how he jumps forward to wipe the sweat from her brow as she begins to play the piano.

I must admit I was initially disappointed by the film’s grainy quality and the poor shot composition. As with the problem of sound synchronization, I suspect Pollack and his crew were not completely prepared for the task.

And yet, the emotion of the performers and the audience soars above the film’s flaws. From time to time, I was tempted to close my eyes, but then I remembered to look and enjoy the display of amazing grace in song and spirit. (Time, Neon)

About the Author

Otto Selles teaches French at Calvin College, Grand Rapids, Mich., and attends Neland Avenue Christian Reformed Church in Grand Rapids.