The first time I saw Roma, I watched it on Netflix with my husband. We watched it over two nights with a number of interruptions. When the final credits rolled, it was late and we were tired. As he clicked off the TV, he offered his one-word review: “Weird.” My take was different, but not completely. Roma is a gorgeous film. It feels exceedingly real as a 70s period drama and centers on a kind and sympathetic protagonist. It is also a long, slow-moving, subtitled, black-and-white movie that includes a couple of rather bizarre scenes. Our method of watching it was definitely not the preferred way to see it (or any other film, for that matter).

The second time I watched it on Netflix I was alone and giving it my full attention—a completely different experience.

The film revolves around a young Mixtec woman named Cleo, the maid for a doctor’s family in Mexico City. Sometimes she seems to be treated as part of the family by both the mother, Sofia, and the children; at other times she is definitely not. She cleans, she launders, she serves. She calms, she placates, and she shows these four children a love that goes far beyond the responsibilities of the job.

When the family watches television together, she sits on a cushion on the floor next to the sofa. The boy next to her sweetly puts his arm around her, but since she is on the floor, you can’t help but wonder if it is more like he is petting his favorite dog rather than embracing a family member. Moments after she gets comfortable, Sofia asks Cleo to get tea for her husband.

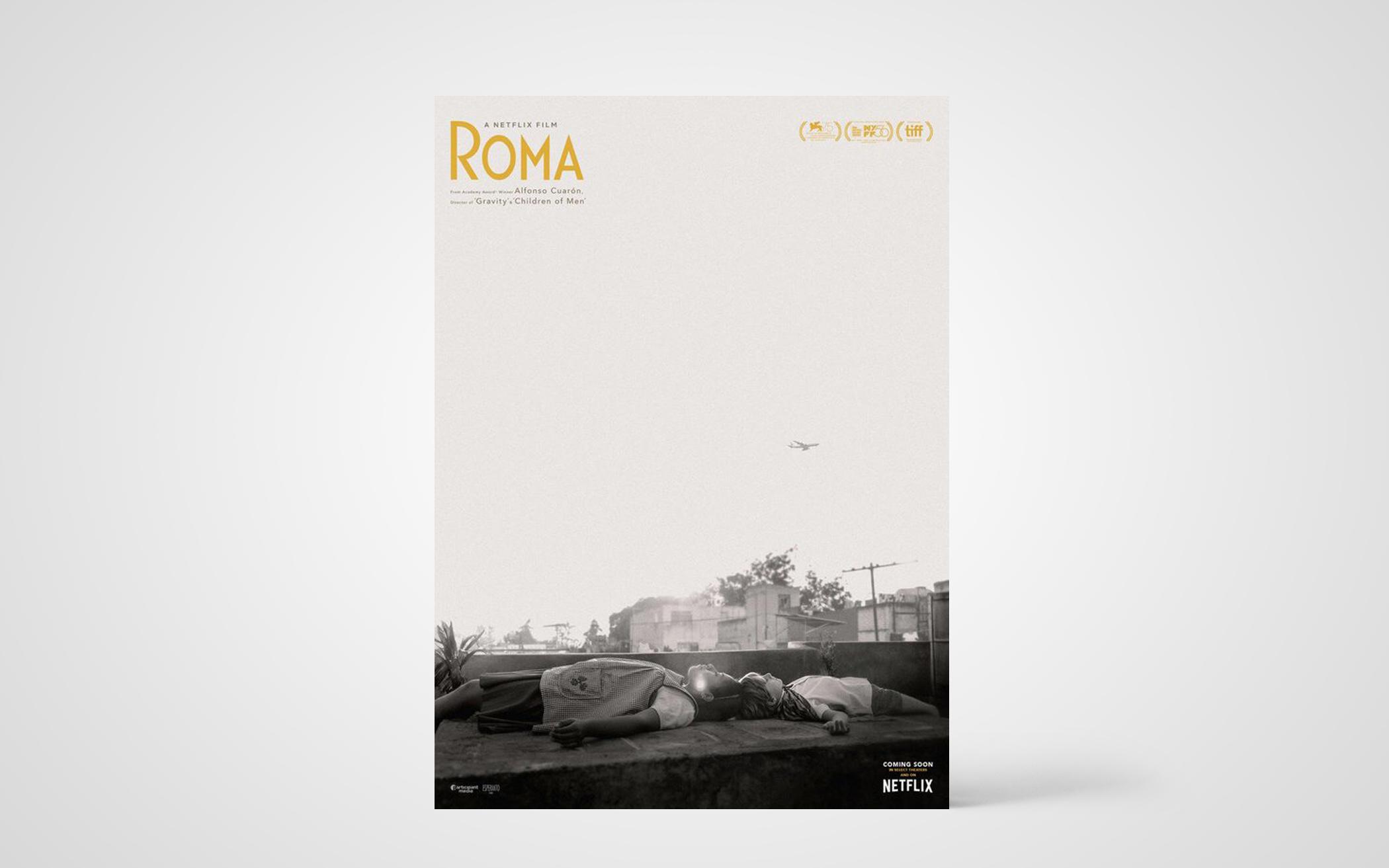

During her daily work, Cleo ascends and descends from the family area upstairs; she ascends further to the roof to wash laundry. On the roof, she steps away from her labors to play dead with young Pepe. Lying on their backs and looking at the sky, she tells him, “I like being dead.” The camera moves on to show a sweeping panorama of what lies outside the walls of their home: more homes like it with more laundry and more maids amid more clotheslines washing what more families have made dirty.

The doctor who employs Cleo drives an enormous Ford Galaxie he can barely get in the driveway, intimating that perhaps he finds his life too small. When he goes to a conference in Quebec, he never comes back, leaving the family to fend for themselves.

Alfonso Cuarón has directed a number of critically acclaimed movies, including Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Children of Men, and Gravity. Each of these films feature a technique he is known for—the long take, which is a camera shot that runs longer than normal. In Roma, he uses long takes throughout the movie, taking viewers into Cleo’s everyday activities at the speed of life.

Airplanes overhead hint at the wealth and mobility Cleo will never achieve while she washes dog feces from the narrow, enclosed driveway. Like the many birds caged in the yard, she is trapped, still alive, and still singing. At the end of the day she settles the children, turns off the lights, and goes back out and down to the small room she shares with Adela, the cook. They get ready for bed in the dark because Sofia’s mother does not like to see their light.

The rest of the movie follows Cleo and the family through a number of challenges and terrible events. The events reinforce her need for a fuller human connection, her vulnerability to forces that are out of her control, and the way the family depends on her even as they sometimes treat her as a glorified appliance.

Roma is an intimate look at daily life and the often unnoticed people who make it happen. It shines a light on the disparity between the privileged family and Cleo’s precarious position. Further, it demonstrates the powerlessness all of the women have in a male-dominated society. It’s so easy to lose sight of the image of Christ in those around us when we don’t acknowledge their full identity and individuality as people.

If you plan to watch it in the near future, you might want to wait and see if it shows up in your local theater now that it has earned an Oscar nomination for Best Motion Picture—it is sure to be a more powerful experience in that setting. Note that it is rated R particularly for one extended scene of nudity. (Netflix)

About the Author

Kristy Quist is Tuned In editor for The Banner and a member of Neland Ave. CRC in Grand Rapids, Mich.