Winner of the 2020 Oscar for Best Documentary, “American Factory” sets a slightly ironic tone with its title. For this is a story of an American plant run by a Chinese company. In that way, the documentary asks, what is an American factory today? And what is the role of a worker, American or Chinese, in our global economy?

The film begins with images of the 2008 closing of the GM plant in Moraine, Ohio, a suburb of Dayton. At the closing ceremony, a speaker praises U.S. workers: “None better. They know how to get the job done.” But that praise is followed by a title noting the sad reality that the plant closure led to the loss of more than 10,000 jobs in the area. A second title appears to explain how, during the recession, Chinese companies snapped up U.S. properties.

Jump to 2015 and the new optimism brought by Chairman Cao, the billionaire founder and CEO of Fuyao Glass Industry in China, who buys out the plant to open up an automotive glass factory. In rosy terms, a recruiter says the company’s plan is to meld American and Chinese culture to create “a truly global organization.” What follows, however, is a catalog of cross-cultural misunderstandings between the American workforce and their Chinese supervisors.

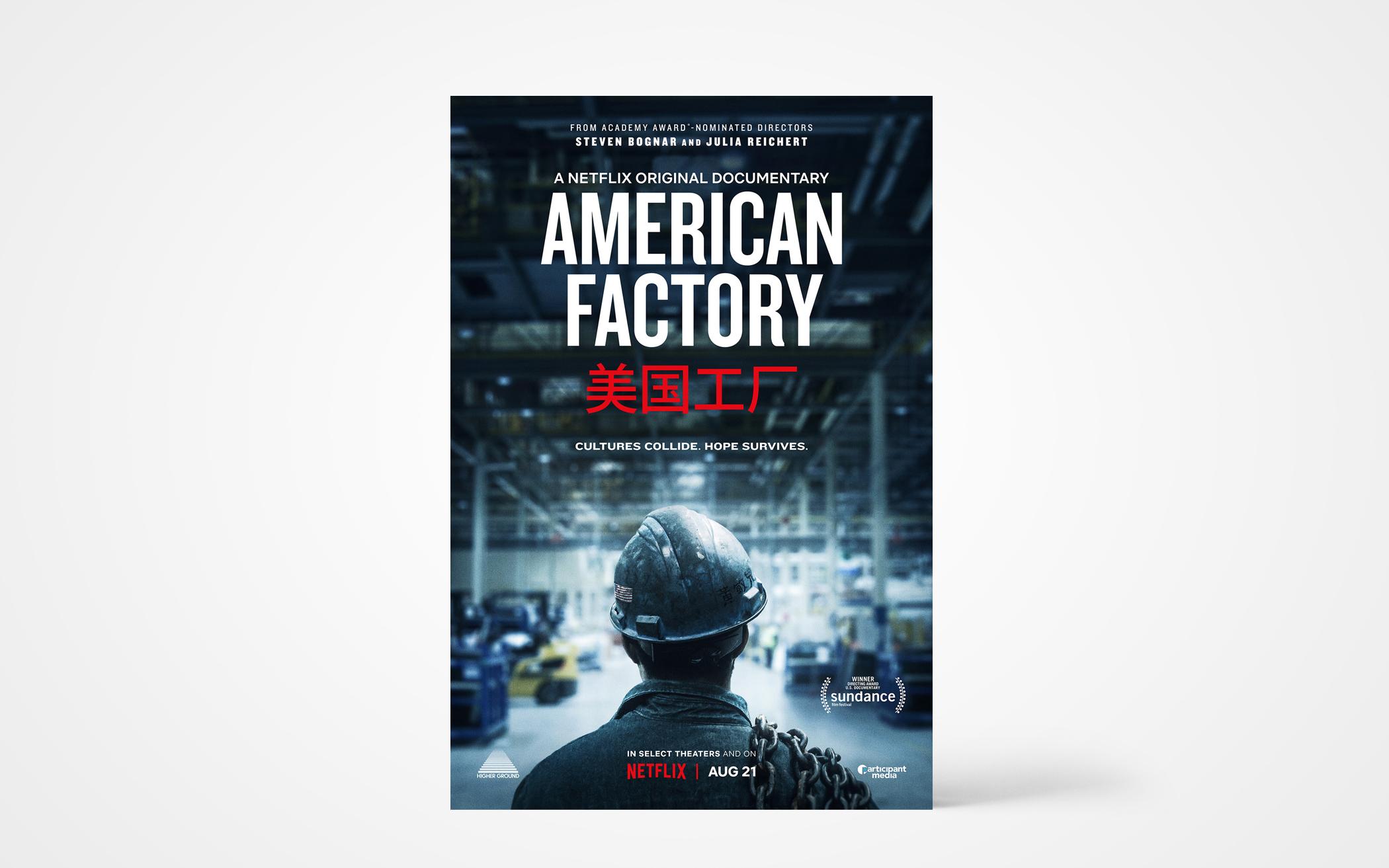

Veteran directors Steven Bognar and Julia Reichert were well-prepared to produce this documentary. In 2009, they made The Last Truck: Closing of a GM Plant that chronicles the final days of the Moraine plant and provides this film’s initial footage. Somehow, they managed in this documentary to catch both the American and Chinese workers, and even Chairman Cao, in their most candid moments.

Bognar and Reichart don’t offer any direct commentary, but allow the images and people to speak for themselves. This strategy creates often a jarring contrast in perspectives. The directors stand, though, clearly in support of the workers’ desire for a piece of the American dream through a well-paying job. The film also represents the first movie made for Netflix through Barack and Michelle Obama’s production company Higher Ground. Look for the conversation, also on Netflix, between the directors and the Obamas as they describe their mutual interest in telling people’s stories, even if that search for a “higher ground” will reveal “cultural clashes.”

In terms of such clashes, what will probably surprise and even shock viewers is the disconnect between Cao’s assurances that “the future is bright” and the way he and his management team look down on the American workers as slow, with “fat fingers” and fragile egos. It is not surprising with such attitudes that the optimism of the factory’s founding soon sours. Cao and his management team also expect complete devotion to the company; workers must be ready to sacrifice their weekends and family time for the factory’s fortunes. The American workers soon push back, asking questions about procedures and work safety and begin to argue for a union.

Some of the cultural contrasts are particularly cringeworthy and darkly amusing. The top American supervisors at the Ohio plant have the opportunity to tour a Fuyao plant in China and attend the company’s New Year’s party. Chinese employees perform supremely kitschy song and dance numbers, all to the glory of the company. The fairly physically unfit American team then comes to the stage to lead the crowd to a much less-polished rendition of “YMCA.” The viewer is left to ask, “Is that all America has to offer?”

Basking benevolently in the cult of his personality, chairman Cao comes across initially as a ruthless businessman, ready to squash a union vote and to do whatever’s needed for a healthy profit. At one point, he states, “The point of living is to work.” It is of course a 21st-century irony that a Chinese billionaire, whose company has close ties to the communist party, arrives in America to preach the merits of capitalism. And yet, Cao is also shown as a devout Buddhist who misses the simple pleasures of nature he enjoyed as a child. With all the factories he has built and their impact on the environment, he says, “I don’t know if I’m a contributor or a sinner.” Again, it is to the directors’ credit that they were able to portray the complexity of people, American and Chinese.

Look for the scenes showing a Chinese supervisor named Wong, a first-rate worker who is admired by his American counterparts. He has left his wife and children in China to work for two years in Ohio. Despite his incredible work ethic, Wong also wonders about how China has changed, from a culture where most families worried about getting enough food for the day to a culture where “we want it all.” Some of the final scenes show Wong living in the U.S. with his family—and you wonder, how will the Chinese and American dreams combine?

In the context of current U.S.-China unease, as well as the pandemic and the ensuing global slowdown, this documentary offers the opportunity to reconsider how we can communicate better despite our cultural, linguistic, and political differences. It also gives us the chance to think more deeply about the point of living and working. (Netflix, rated TV-14 for language, smoking)

About the Author

Otto Selles teaches French at Calvin College, Grand Rapids, Mich., and attends Neland Avenue Christian Reformed Church in Grand Rapids.