If Netflix’s algorithms and offerings shed some light on our current obsessions, we might find ourselves asking, Is society today really all that secular? After all, a quick glance through its categories reveals that its most popular programs feature some element of the metaphysical. From Stranger Things and The Good Place to newer additions like The Witcher and Locke & Key, we seem preoccupied with stories that suggest life amounts to more than what a materialist worldview accounts for.

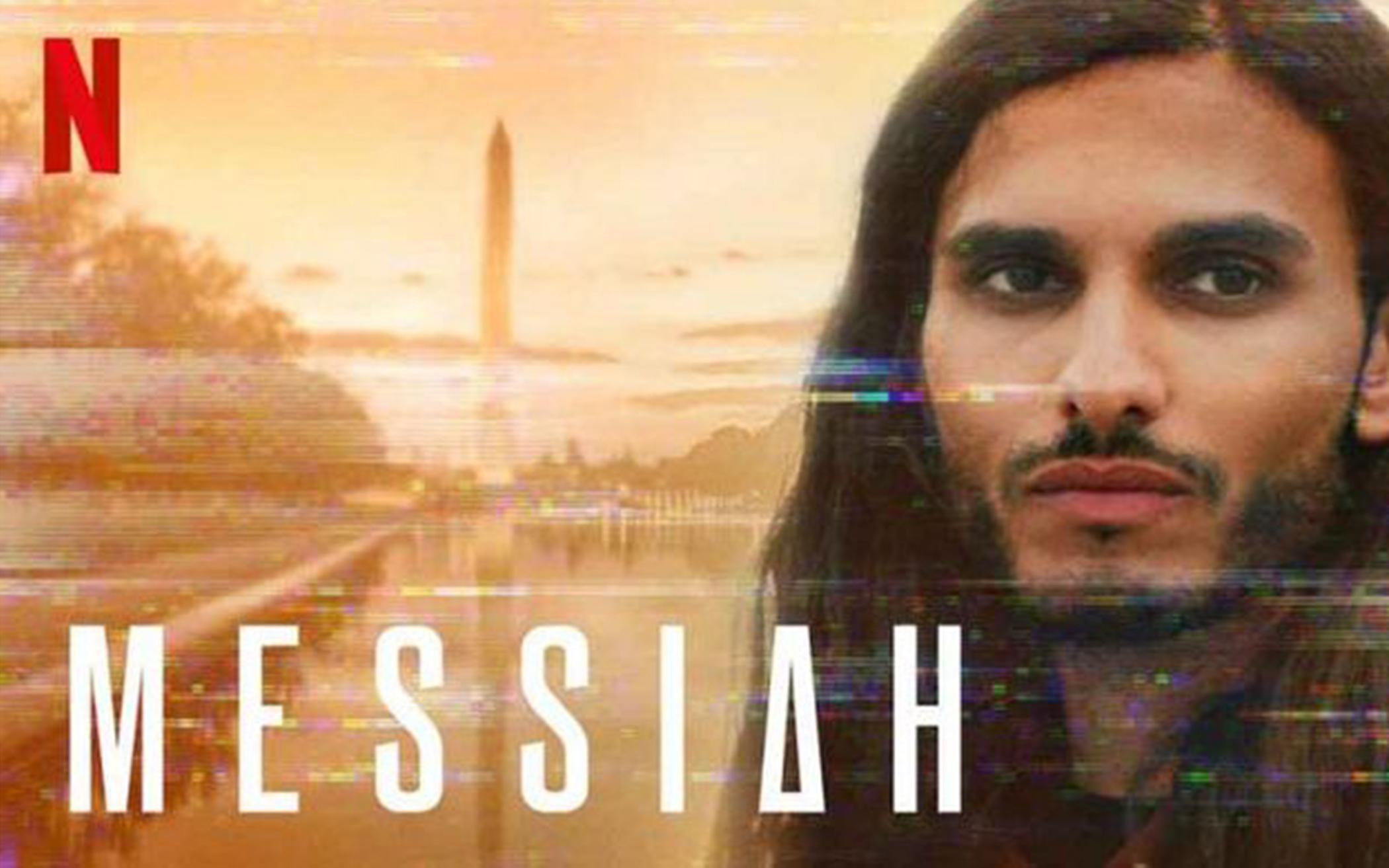

In keeping with this trend, Michael Petroni’s new show Messiah sets out to examine how we might react to the transcendent breaking into our modern world, specifically in the form of someone who looked and acted an awful lot like Jesus. This, the central conceit of the show, makes for an intriguing premise. The first episode introduces us to Al-Mahih, a messiah-like character who shows up in Damascus, assuring the local residents that ISIS will not capture their city. As he delivers this message, a giant sandstorm rolls in, one that lasts an entire month and ultimately thwarts the Islamic State’s military efforts. His first miracle.

Al-Mahih then leads a group of Muslims to Israel, gets arrested by Israeli border police, mysteriously escapes his captors, preaches a sermon at the Dome of the Rock, and appears to heal a young child—the first couple of episodes are action-packed—all before the plot moves to America and slows down considerably. For the remainder of the season, we follow Al-Mahih’s travels in the U.S. (his arrival there counts as another mystery). We watch him follow, in the states , a trajectory much like the one he charted in the Middle East, albeit performing miracles in a more overtly Christian manner and context. For example, his arrival seems to protect a Texan church from a devastating tornado, and after leading a large group of followers to Washington, he walks on the water of the reflection pool at the Lincoln Memorial.

Much of the drama from this point on revolves around different characters’ reactions to Al-Mahih. Could he truly be a new messiah (as Texan pastor Felix and his daughter Rebecca want to believe) or is he nothing more than a charlatan (the view held by Felix’s wife and CIA agent Eva Geller)? In these competing reactions, Messiah finds its greatest potential, asking its viewers to confront the same dilemma: what would we do if faced with someone claiming a special relationship to God, performing unbelievable acts, but contradicting our notions of what a messiah should be—that is, something other than a man in Nike clothes who dodges questions with infuriating obliqueness.

At its best, the show puts its viewers in a similar position of Jesus’s own followers. For instance, when a prostitute, hired by shady forces, tries to seduce and discredit Al-Mahih, his response is direct, almost confrontational, yet ultimately gentle and loving. This moment, a genuinely moving one, offers a glimpse of what it might be like to encounter a surprising savior.

Ultimately, though, the narrative disappoints. Some of this has to do with the character of Al-Mahih himself. Unlike the Jesus of Scripture, whose unexpected answers end up revealing more, not less, about himself, Al-Mahih’s words echo Scripture only loosely, and all too often, end up sounding more like platitudes that would fit comfortably next to a Coexist bumper-sticker.

In part, the show suffers from the same kind of problems that Lost (another fantastical show) grappled with: it’s one thing to build a mystery upon an engaging premise; it’s another thing to conclude it—to draw meaning from the supernatural happenings afoot. To be fair, Messiah might provide more direction in future episodes, but its first season ends with more questions than answers. And my guess is that whenever the show concludes, we’ll still be left wondering who Al-Mahih really is, the implication being that he is whoever we want him to be. In this way, then, Messiah really does reflect our cultural values—we long for something transcendent, as long as we get the final word. (Rated TV-MA for language, brief sexual scene, Netflix)

About the Author

Andrew Zwart lives in Grand Rapids, Mich., and is director of interdisciplinary studies at Kuyper College. He enjoys gardening, impromptu dance parties with his wife and two boys, and taking walks while listening to podcasts.