As I Was Saying is a forum for a variety of perspectives to foster faith-related conversations among our readers with the goal of mutual learning, even in disagreement. Apart from articles written by editorial staff, these perspectives do not necessarily reflect the views of The Banner. The Banner has a subscription to republish articles from Religion News Service. This commentary by Mark Silk was published Aug. 15 on religionnews.com.

Editor's Note: This opinion piece by Mark Silk for Religion News Service focuses on an issue that the Christian Reformed Church synod addressed in 2025. Synod voted unanimously to "deplore the legalization and practice of medically assisted suicide as well as the efforts to expand it to include minors, and those suffering solely from psychological disabilities.”

(RNS) — No country in the world has gone as far as Canada in enabling people to die if they want to. And a lot of Canadians want to. In 2023, the last year for which statistics are available, 15,343 of them had their lives terminated by way of the country’s Medical Assistance in Dying law—nearly 5% of the total number of deaths in the country.

In the September issue of The Atlantic magazine, staff writer Elaina Plott Calabro reviews Canada’s MAID experience and, within the bounds of reportorial balance, suggests it is a bad thing. You can understand her qualms.

Ten years ago, the Canadian supreme court overturned a criminal ban on medically assisted death. Initially, a person’s natural demise had to be “reasonably foreseeable” to be considered eligible for MAID, but in 2021 that requirement was removed. Individuals with chronic, debilitating conditions whose death was not imminent were allowed to seek MAID under what was termed Track 2.

It is expected that the law will be changed in the near future to permit mature minors and individuals with mental illness to choose MAID and, possibly, to allow people to make advance requests for MAID in anticipation of being incapable of requesting it later.

So far as Calabro is concerned, the problem is that Canada has made the value of patient autonomy “paramount, allowing Canada’s MAID advocates to push for expansion in terms that brook no argument, refracted through the language of equality, access, and compassion.”

“This is,” she writes, “the story of an ideology in motion, of what happens when a nation enshrines a right before reckoning with the totality of its logic. If autonomy in death is sacrosanct, is there anyone who shouldn’t be helped to die?”

Actually, yes. MAID does provide procedural safeguards, and more stringent ones for the individuals in Track 2. In all cases, two independent medical practitioners have to give their consent for the procedure, and every year there are hundreds of cases where applicants are deemed ineligible for one reason or another, including being incapable of making decisions about their health or not being informed of alternative means of relieving their suffering or being subject to external pressure.

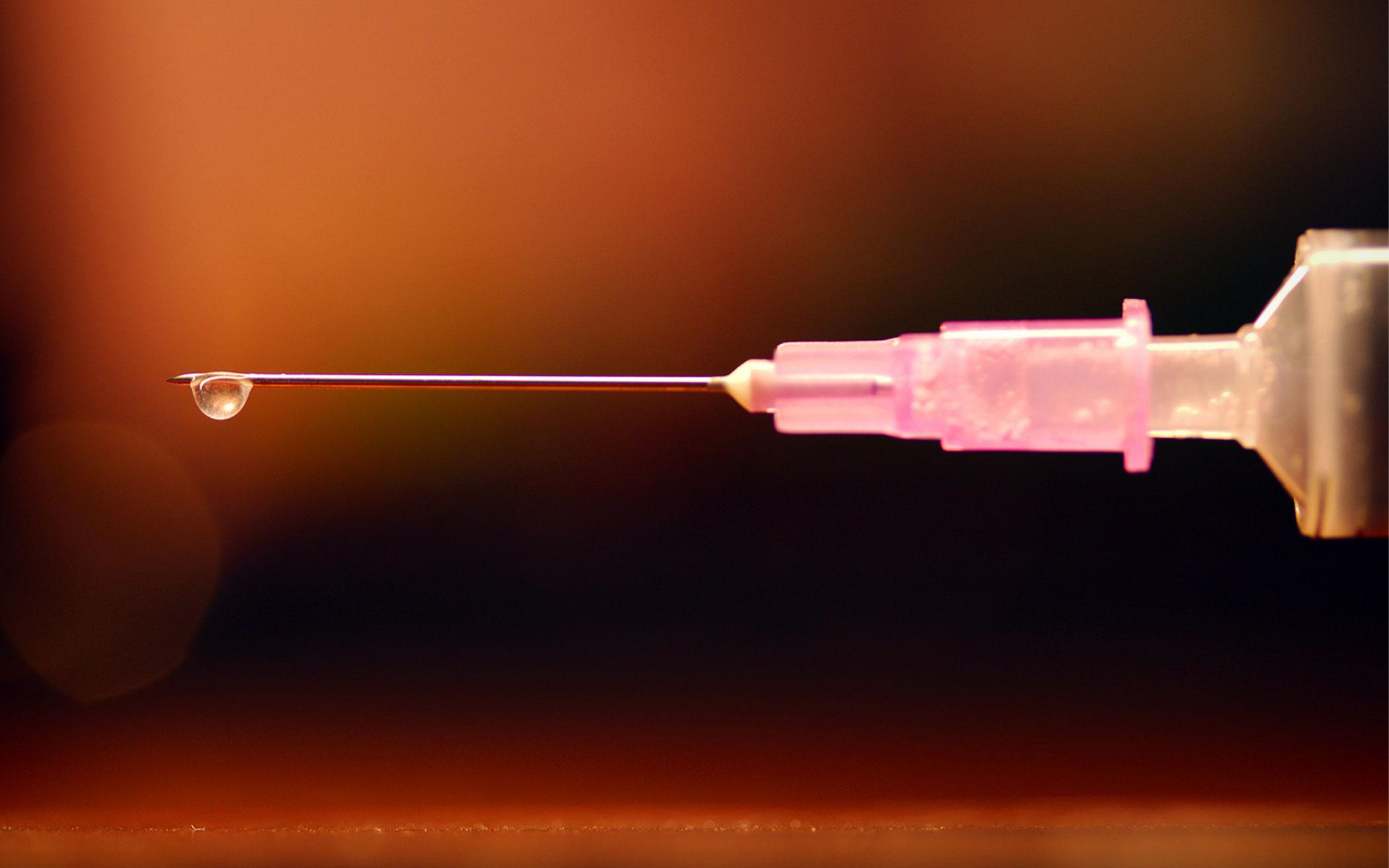

But as Calabro sees it, these safeguards are not what limits MAID from wider use but, rather, the reluctance of clinicians to serve as providers. (In nearly all cases, death is via a series of shots administered by a clinician, as opposed to a patient being helped to commit suicide.) That has been particularly true in the case of Track 2, 30% of whose provisions were made by just 89 of the 2,200 MAID practitioners in 2023.

As one of the 89 said in explaining his willingness to overcome his discomfort with ending the life of someone who is not actually dying: “Once you accept that people ought to have autonomy—once you accept that life is not sacred and something that can only be taken by God, a being I don’t believe in—then, if you’re in that work, some of us have to go forward and say, ‘We’ll do it.'”

There’s little question that the decline in religious belief has contributed significantly to the rise in the numbers of people seeking medical assistance in dying, not only in Canada but in the small number of other countries that permit the practice.

In the Netherlands, whose MAID law is similar to Canada’s, the percentage of MAID deaths has increased from 1.3% to 5.4% since its law went into effect in 2002, as the non-religious population rose from 40% to 56%. In Switzerland, where assisted suicide (but not euthanasia) has been legal since 1942, the percentage of assisted suicide deaths has increased tenfold, from .2% to 2% since 2000, even as the non-religious population has grown from 11% to more than one-third.

In Canada, this is most striking in Quebec, where the abandonment of Catholicism by much of the population has resulted in, for example, 75% of Quebecers who now think abortion is acceptable, as opposed to 8% who think it isn’t—making Quebec the most pro-choice province in the country. Quebec also has Canada’s highest rate of MAID provision—7.2% of all deaths in the province, which in fact is the highest rate of any jurisdiction in the world. While less than a quarter of Canada’s population lives in Quebec, almost 40% of MAID provisions take place there.

No doubt, more safeguards (longer waiting periods, tougher permission standards) would reduce the number of MAID cases in Canada. But these would run up against the views of the Canadian citizenry. According to the most recent survey (2023):

• 84% support the court decision allowing MAID.

• 78% support the 2021 removal of the “reasonably foreseeable” requirement.

• 82% support advance requests for those with a grievous and irremediable condition, although down slightly (-3) this year.

• 72% support advance requests even if no grievous or irremediable condition exists, down five points from last year.

• 71% support the ability for mature minors to request and be considered eligible for MAID, providing they meet all criteria under the law.

• 80% support access to MAID for those suffering solely from a severe mental illness.

If the value of patient autonomy is backed up by the value of democratic decision-making, where does that leave the value of preserving life at all costs?

(The views expressed in this opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of RNS)

Editor's Note: This opinion piece by Mark Silk for Religion News Service focuses on an issue that the Christian Reformed Church synod addressed in 2025. Synod voted unanimously to "deplore the legalization and practice of medically assisted suicide as well as the efforts to expand it to include minors, and those suffering solely from psychological disabilities.”

About the Author

Religion News Service is an independent, nonprofit and award-winning source of global news on religion, spirituality, culture and ethics.