As I Was Saying is a forum for a variety of perspectives to foster faith-related conversations among our readers with the goal of mutual learning, even in disagreement. Apart from articles written by editorial staff, these perspectives do not necessarily reflect the views of The Banner. This particular column is a commentary from Religion News Service.

(RNS) — According to mental health professionals, when human beings encounter a threat we respond in one of three ways: fight, flight, or freeze.

We can choose to confront the threat by fighting, either physically or verbally. We can run away from the threat in an act of self preservation; again, this can be literal or it can be an emotional and psychological retreat. Finally, we can freeze, an experience of physical or psychic paralysis that won’t let us fight or flee but temporarily immobilizes us.

The fight, flight, or freeze reflex may kick in when people of conscience see or hear about the latest incident of an African American killed. I had this reaction when I first saw the video of George Floyd’s killing this week. A white cop calmly pressing his knee against the back of the neck of a prostrate Floyd, who was black. Floyd pleaded with the officer, “I can’t breathe,” until Floyd lost consciousness and soon died.

Another human being reduced to hashtags: #JusticeforGeorge and #Icantbreathe

In the flurry of social media posts once the video became public, many people expressed a sense of helplessness. They said they did not know what to say or do. On Twitter, I tried to express my reaction this way:

“I’m numb. The kind of numb that doesn’t mean you can’t feel anything but that you feel all the things at once and don’t know how to name it or what to do about it."

A numbness, like when you can’t feel your hands after being outside in the cold without gloves, is honest, even predictable. But as I probed my reaction, I actually discovered a handful of actions that might help get us unfrozen.

Over the past few years, I’ve developed a model called the A.R.C. of Racial Justice that I believe can help us work through feelings of helplessness (and numbness) when we witness racism. It stands for Awareness, Relationships and Commitment. Breaking down racial justice actions into these three areas makes the prospect of moving again more manageable.

Awareness

So often when we hear about another notorious incident of white supremacy and violence enacted upon black bodies, we get flooded with emotions: anger, despondency, fear, frustration.

We need to sit with the feelings that come in the wake of an injustice. Taking external action without prior or simultaneous inward action will leave us working from an empty reservoir of emotional fuel.

We need to do the hard work of heart work. This fits under the “awareness” heading because we are increasing our self-knowledge.

When he saw my tweet about feeling numb, a therapist friend of mine recommended writing a letter to whiteness … and then burning it. He said, “The trauma needs somewhere to go and be released.”

I did this and it felt so good. I put words to my inchoate feelings and articulated my emotions. And I really liked the burning part. Black people need to do this because, as James Baldwin said, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively aware is to be in a rage almost all the time.” We need to put that rage somewhere.

White folks can do something similar. Writing down your feelings in these moments is healthy. Maybe you have questions of yourself or others that you haven’t been able to verbalize yet. Maybe you have a sense of shame and guilt over your white privilege that you need to put into sentences and paragraphs.

Do it. Put it all out there. Then burn it.

Racism traumatizes both the oppressed and the oppressor, and that trauma needs to go somewhere and be released.

Relationships

Earlier this week, I learned a new hashtag: #BirdwatchingWhileBlack. It came about because a white woman called the cops on a black man, Christian Cooper, in New York’s Central Park while he was out birdwatching. The woman had a dog that was not on a leash, as the park rules required. When Cooper asked her to leash the dog, she decided to call the police and act as if the black man was a threat to her physical safety. Good thing the man had his cellphone camera, so we could see what actually happened.

In the aftermath of #BirdwatchingWhileBlack and the unwelcome reminder that black folk can literally be doing anything and still become the subject of surveillance and abuse, all I wanted to do was be close to my child. I packed up early from work and spent the rest of the night just hanging out and pouring into that relationship.

In a white supremacist society, Black love is a radical act. Building relationships with other black people and people of color can be a way to fight back against the despair that hounds us.

So, black people, love each other. Laugh together. Get on a Zoom call. Write letters. Call. Celebrate the relationships you have with other black folks who know what it’s like to have their bodies perceived as threats yet can find reasons for hope, joy, and love anyway.

White people, invest in the black people you know. Ever since the #BlackLivesMatter movement, which served as a racial awakening for a lot of white people, I’ve had a handful of white folks call, text or email me whenever another horrendous act of racism makes national headlines. They’re not asking for anything. They’re expressing their grief along with mine, they’re asking what I need, they’re letting me know they’re praying for me.

Their words don’t bring dead Black bodies to life. They don’t indict police officers for murder. They don’t change the danger I face as a black man whenever I leave my house. But they do matter to me. They are a slight sign that others know this is hard, and they don’t want me to feel alone.

So reach out. Be gentle. Don’t demand attention or affirmation. Just let the people of color in your life know you’re present when they’re in pain, and that you’re in pain, too.

Commitment

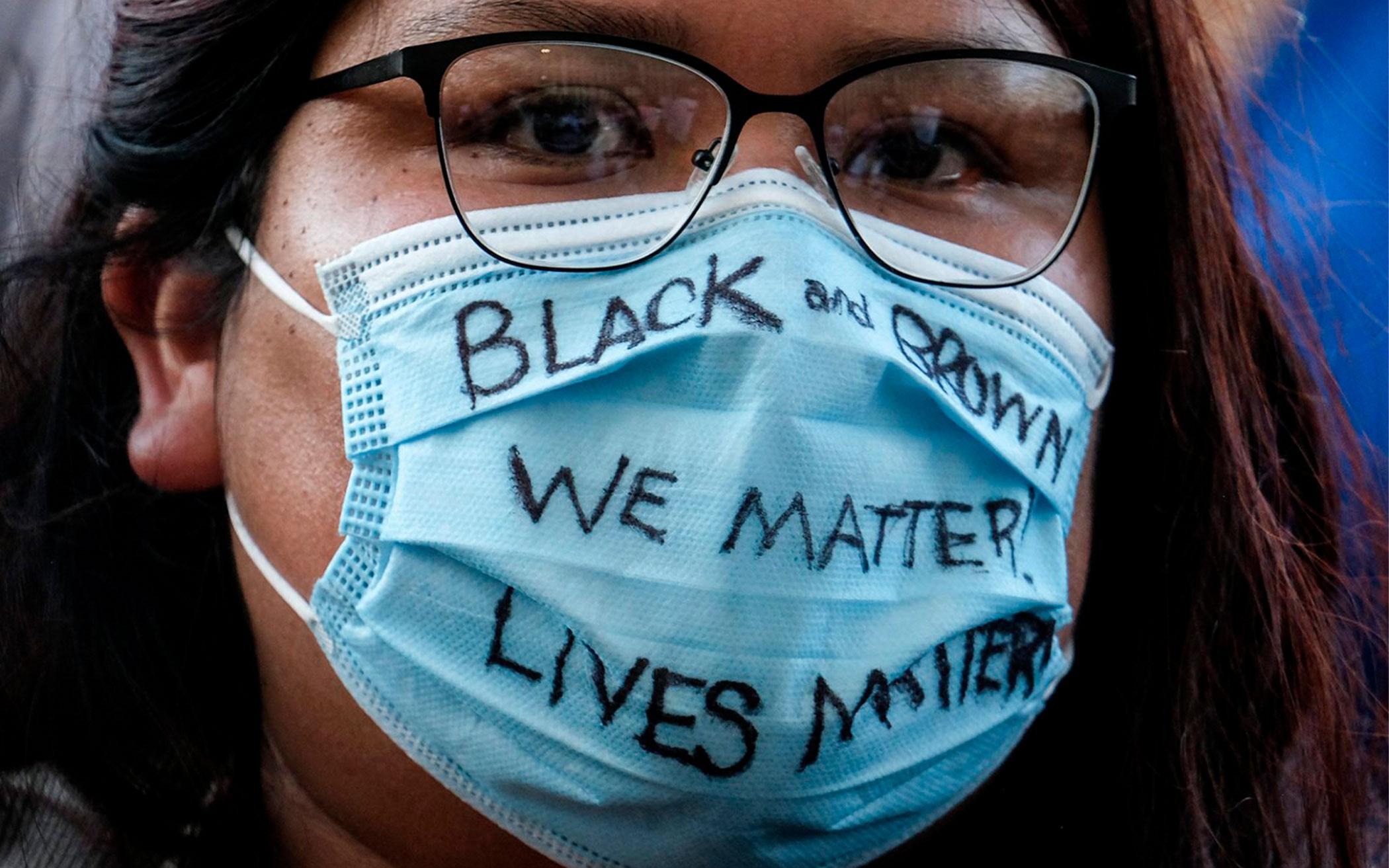

That feeling of being frozen in the face of black death comes from the regularity of the tragedy. It’s 2020. I vividly recall the national moment when 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was killed for having brown skin and wearing a hoodie—and became a proxy for everyone’s thoughts about race and justice in America. That was eight years ago. Then there was a string of black deaths, from Sandra Bland and Alton Sterling to Rekia Boyd and the Emanuel Nine.

When does it ever stop? Does anything we do make a difference? Will black lives ever matter?

If we want to see widespread change in the racial structure of this nation, then we have to commit to changing racist policies and practices. In the case of George Floyd’s death, which involved yet another police officer, we need to deeply probe policing in this country.

Activists have an abundance of recommendations. Campaign Zero, a nonprofit dedicated to ending police violence, lists 10 practices to achieve this goal, including establishing independent review boards for local police departments; better training for police, including implicit bias and de-escalation training; and demilitarizing the police force’s weaponry.

Beyond reforming policing as it currently exists, some activists insist that the entire enterprise, rooted as it is in slave patrols and controlling black bodies, should be abolished. They advocate defunding police departments and diverting the money to other areas such as mental health care, using restorative justice teams for help resolving conflicts, and decriminalizing many behaviors so that law enforcement is not required.

Some actions to affect policing at a broad level include:

- Financially supporting organizations dedicated to eliminating police violence

- Calling state and local officials to advocate for changes in their law enforcement platform

- Meeting with local mayors, council members, and law enforcement leaders to hear their thoughts on policing and the community and to make your thoughts known

- Demanding public transparency in the negotiation of police union contracts

Acclaimed writer Anne Lamott keeps a 1-inch picture frame on the desk where she writes. Whenever she struggles getting started writing, she looks at that 1-inch picture frame. “And it reminds me that all I have to do is to write down as much as I can see through a one-inch picture frame.”

We can do the same with fighting for racial justice.

Whenever the massive problem of fighting white supremacy, racism or police violence freezes us in place, we don’t need a grand vision for reform and revolution. All we have to do is think of a “1-inch” action to get us going. It can be increasing your awareness of an issue, building a relationship, or committing to reforming a policy or practice. If we keep going, then the 1-inch actions we take to fight racism can paint a beautiful portrait of justice and equity.

The Banner has a subscription to Religion News Service and occasionally re-publishes articles of wide Christian interest, according to the license. The original story can be found here.

© 2020 Religion News Service

About the Author

Jemar Tisby is president of The Witness: A Black Christian Collective, where he writes about race, religion, and culture. He is cohost of the Pass the Mic podcast and a doctoral student in history at the University of Mississippi. Follow him on Twitter @ JemarTisby.