One day, when all our people were gone out to their works as usual, and only I and my dear sister were left to mind the house, two men and a woman got over our walls and in a moment seized us both, and, without giving us time to cry out, or make resistance, they stopped our mouths, and ran off with us into the nearest wood. Here they tied our hands, and continued to carry us as far as they could, till night came on, when we reached a small house where the robbers halted for refreshment, and spent the night. We were then unbound, but were unable to take any food; and, being quite overpowered by fatigue and grief, our only relief was some sleep.

—Olaudah Equiano, kidnapped by slavers at age 8 (A Journey in Chains, Library of Congress)

After what could be a months-long march to the sea, abducted Africans were kept in coastal fortresses until slave ships arrived. One of those fortresses is on Bunce Island, Sierra Leone.

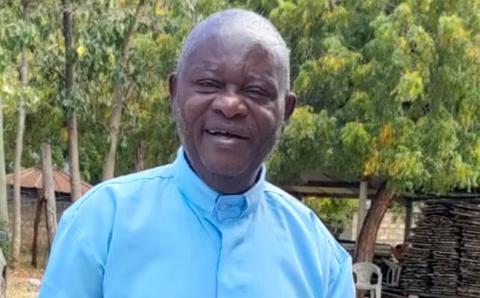

For the past several years, I have frequently traveled to Sierra Leone in my capacity as a consultant with World Renew. The purpose of my travels is to connect with World Renew’s partner group, Christian Extension Services, which has been involved in exemplary community development work for many years. I had heard about Bunce Island, but I had not ventured there because my time in Sierra Leone was usually quite full with village visits and staff meetings. But on one recent trip, my friend and guide Milton Marah accompanied me to Bunce Island, a hub of West African slave trade from 1670-1808.

Bunce Island is a bit of land about five kilometers square (not quite two square miles) situated where the Sierra Leone River runs westward into Tagrin Bay and then the Atlantic Ocean. Its crumbling jails and staging grounds are now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, an artifact of the slave trade that enriched so many nations and raped Africa in the process. I’m one of those who has benefited indirectly from such injustice, so this pilgrimage to Bunce was a painful experience.

From the airport town of Lungi, Milton and I traveled to Pepel, a town along the bay leading to the Atlantic. There we inquired about visiting Bunce Island, visible in the distance. A village leader emerged and told us we were among the few people, mostly African-Americans, who visit the island—only about a dozen per month. We paid for the trip and got into the home-crafted boat made from local timbers around eight meters long and equipped with an outboard motor.

The young men taking us to the island responded to a few questions about what it was like to live as fishermen; then we settled into silence. After a 20-minute ride over mostly calm water, we arrived and disembarked on the island’s dock. Only a plaque and eerie silence greeted us as we stepped onto Bunce Island. No one lives on this lush island despite the recently built guard house that’s been mostly unoccupied since its construction, our guides told us.

We followed the only path onto the island and encountered a few more plaques describing the island’s history. Stiff, stilted language attempted to put into meaning an inhumanity that defies description.

The path then led up a hill to a crumbling fort with large and small chambers and open areas where the slaves were assembled when the slave buyers arrived to select their cargo. Our guides were respectful and quietly spoke to us what they knew of the place, at the same time wondering at how people could sell people and at their own people’s involvement as accomplices to the European and American kidnappers.

One of the plaques stated that ships from various countries trafficked more than 30,000 people in the 140 years Bunce Island operated as a holding space. In my mind I could hear the cries and groans of helplessly trapped people echoing among the ruins.

The trail next brought us to a graveyard of mostly unmarked stones. Among the more legible granite headstones was one for a captain that proclaimed him to be “a man of upright character, beloved by his companions.”

Monkeys scampered in the trees and birds whirled overhead as the natural world closed in on this mostly forgotten piece of inhumanity. Trees and brush were beginning to swallow the ruins, as if to hide the shameful evidence. One of the buildings now resembles a gaping skull.

We walked quietly back to the boat, overcome with the emotions of what we had seen and deep in our own thoughts. I tried to convey to my colleague and guides how terrible I felt about this monumental evil, this systemic rot that governments and churches enabled. Once back in the boat, our guides watched us carefully.

“What message would you have us take of this island?” I asked.

The answer: “That slavery happened, and that it must never happen again.”

I looked down at the floor of the boat, a few inches above the hull itself. Between the two layers of boards I could see seawater sloshing, murky and dirty, and I thought of the ships carrying people as cargo, stacked like logs between decks with their cries of pain ignored.

Approaching Pepel, we saw other fishing boats heading toward the dock and were told these were fishermen returning home—not from a fishing trip, but from another task we soon learned about. We saw hundreds of people gathered where only a few had been when we set off for the island. From a distance we heard anguished wailing and screaming. Our boat slowed to let other vessels by—boats full of men and women bent over in grief.

We looked at our guides for an explanation. They told us a fisherman had been lost at sea, and these boats were full of friends and family who had gone to look for him. The boats were now returning at the end of a sad day with neither a corpse nor a rescued sailor, and the entire town had turned out to hear the news. The tear-stained crowd was shocked to hear someone they knew was missing and likely drowned. We did not hear the details, but we felt the weight and grief of an entire community.

Stepping out of our boat onto the dock, we headed for our vehicle quite unnoticed by a mourning village. Milton and I thanked our new friends, then drove away, stunned by the tragic timing of events. The visit to Bunce Island had filled my imagination with the cries of anguish from the past that were then eerily reflected in the voices of people in the same area mourning yet another loss.

This visit was for me a powerful reminder of the impact of slavery in Sierra Leone and serves as a connection to those in North America whose lives were shaped by this place. It’s also a scathing reminder that human trafficking is still not over. It’s time to awaken.

About the Author

Daniel Friesen lives in Winnipeg and is a sustainable development consultant working with World Renew and other organizations. He and his wife, Helen, have four adult children and are a part of the First Nations Community Church.