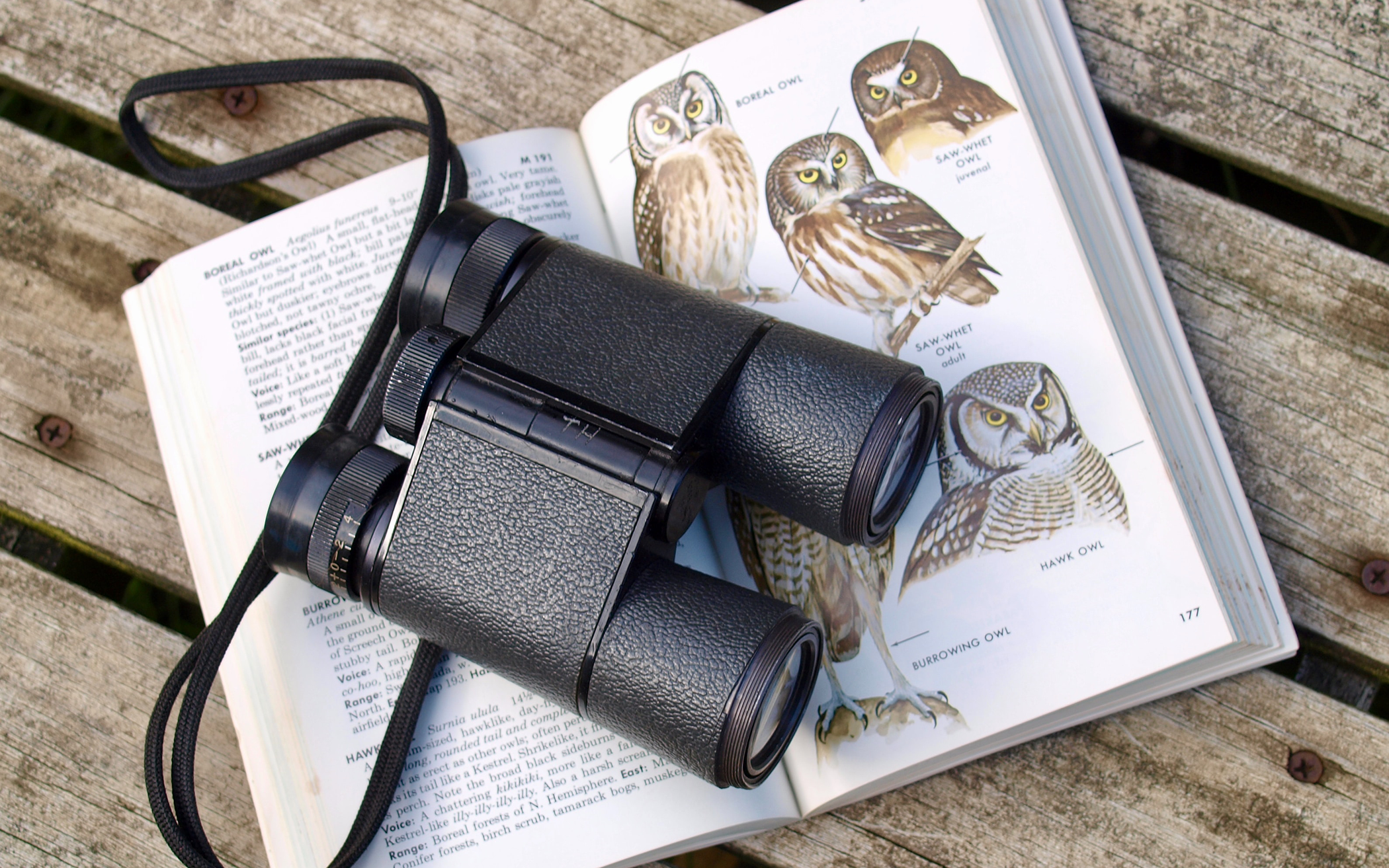

Besides having an uncountable number of books to borrow, our local library has started to loan STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) kits. One of these kits is a backpack filled with all the equipment needed for a budding ornithologist: a map of local parks and waterways, a bird identification book, and of course a pair of high-powered binoculars. My animal-loving middle daughter was the first in our family to borrow this bird-watching kit. When she got home, it did not take her long to start looking out the windows toward the backyard.

“Dad, I see a robin!” she announced. “These binoculars make it so clear it’s like it’s in our house with us!”

Glad that there were still some panes of glass between the birds and my living room, I watched as my daughter gazed in delight as other birds soon joined the robin at the bird feeder. Soon the commotion drew my son’s attention. His constant curiosity fits right into the engineering part of STEM. Instead of asking to look at the birds, he engaged me in his usual style: a game of 20 Questions: “How do binoculars work, Dad? How come things are so big? Why don’t glasses make things look so big? Why do binoculars have two eye holes, but a pirate scope only has one?”

I gave my 7-year-old son a brief explanation of lenses, mirrors, and light, which seemed to satisfy his curiosity—until his brain finished processing and he hit me with another round of questions: “Why do mirrors show things backward? Why don’t mirrors make things bigger or smaller? Why do binoculars only make things bigger?” Away we went again.

All this talk of mirrors and binoculars reminded me of a saying that our pastor uses from the pulpit on occasion: “When you come to church next week, we are going to be looking at [insert passage here]. Please make sure to pack your ‘mirror Bibles’, and leave your ‘binocular Bibles’ at home.”

Huh? Who has Bibles made of mirrors, or of convex and concave lenses and glass? Seems dangerous to me! But my son’s impromptu game of 20 Questions and the spur-of-the-moment physics lesson helped me begin to truly appreciate what our pastor was wishing for the congregation to understand.

There are two ways we can read the Bible: as if it’s a mirror or as if it’s a pair of binoculars. When our pastor encourages us to bring our “mirror Bibles,” what he’s really telling us is to turn our eyes inward. Let the words of Scripture illuminate the shadows in our lives, and let them bring us to a better understanding of who we truly are and how God sees us. One definition of a mirror is “something that gives a true representation” (Merriam-Webster). Just as a mirror reflects one’s true physical appearance, the Bible, when read thoughtfully and meditatively, will lead people into self-reflection and self-discovery—an introspective view that helps us develop humility, empathy, and a deeper understanding of our faith, our spirituality, and our individual relationships with Jesus.

My pastor also asked us to leave behind our “binocular Bibles.” What are those? While “mirror Bibles” lead to introspection, “binocular Bibles” are focused on the external and limit our view of ourselves. “Binocular Bibles” allow us to see faults and problems with others while ignoring our own. If we use the Bible in this manner, it becomes easy to read a passage and think about all the people in our life who could benefit from its message instead of asking how it applies to ourselves. “Binocular Bibles” easily lead to places of judgment and binary thinking. Using the Bible solely as binoculars might lead to a lack of personal growth and transformation because the focus remains on the perceived flaws of others rather than on our own.

Let’s look at Luke 6:41-42 and imagine how the same passage would be read differently with a “mirror Bible” versus a “binocular Bible.” Someone reading a “mirror Bible” will read the text and become aware of things in their life that need to change. The reflection they see in the Bible will clearly show them the plank that needs to be removed from their own eye. Yet someone using a “binocular Bible” to read the same passage will look outward, see everyone else with planks and specks in their eyes, and feel vindicated in their judgments of others.

Mirrors are a tool to help us build our understanding of ourselves. Without mirrors, we would be unable to see one of the biggest parts of our identity: our own faces. Generally, we can see other faces using just our eyes, but for us to see our own faces, to see our own identities, we must use a mirror.

So the next time you see your reflection in the mirror or use binoculars to watch birds or other animals, be reminded and encouraged to use your “mirror Bibles” and to leave your “binocular Bibles” at home.

Discussion Questions

- When you honestly examine your own habits in responding to sermons, do you notice a tendency to use a “mirror Bible” or a “binocular Bible”?

- Why do you think some people’s default is a “binocular Bible”?

- Can you think of any biblical passages or stories that may support or illustrate the “mirror Bible” approach?

- Can you think of other metaphors or ways to enhance the “mirror Bible” approach to Scripture that can foster our spiritual growth?

About the Author

Dan Veeneman works in the dairy industry as a ventilation specialist. He lives in Abbotsford, B.C., with his wife and three children. He is a member of Gateway Community Church.